|

Abbey veered her sedan to the right to avoid making roadkill of the skunk as they zoomed along the potholed Indiana back-road, causing branches from the hanging trees to scrape side of her ride, and her friend Sara to drop her cigarette on the floor.

“What the hell, Abbey!” Sara yelled. Peggy griped from the back, “Chill out. We’re okay.” “Sorry, all this ghost talk is working me up.” “We all just need to simmer down,” Abbey said, as she re-centered on the narrow road. “Well, slow down first. It’s not like we have to punch in when we get there.” Peggy videotaped it all with a small camera. Later she’d edit the footage for their Midwest Psychic Quest channel on Witchtok. Sara relit her smoke. They’d been in the car over two hours after a crappy day at the salon. Her boss had flaked out again, made her go pick up product on her own dime. As general manager the only perk seemed to be extra hassle and coworkers who talked behind her back. Maybe one day their channel would take off, they’d get some sponsors, ghost hunt and legend trip full-time. It was a dream, but it kept the encroaching winter blues at bay on the dull days of drudgery. The legend tripping videos got the most likes and comments of all their content, and the episode on schedule was a visit to the site of the brutal circus slayings in Euterpe, Indiana, where the Wallbanger Big Top had kept its winter camp and quarters; those quarters now moldered in ruins on an abandoned property behind a strip mall whose last denizens barely stayed in business. They parked their car between Indie CBD and Dollar Discounts, got out, checked flashlights, checked pepper spray, and crept behind the building to look for the hole in the fence that led into the abandoned property. Many others had been there before them. It was easy to follow the trail of beer cans, condom and candy wrappers to the husks of empty outbuildings whose only coats of paint were decades of graffiti. “Let’s get the story on camera.” Peggy set up her light, and prodded Abbey and Sara into place, standing in front of a fading mural of a calliope sprayed on wall that slanted with decay. Sara began. “Before the killings, Ringmaster George Wallbanger often complained he was being driven insane by the sound of the steam calliope. It’s piercing high pitched whistle haunted his dreams. Some researchers have wondered if it was just tinnitus, the gradual loss of his hearing as he aged. Maybe. But when authorities found his journal, a darker picture unfolded. “Wallbanger wrote page after page about the calliope being possessed. He said it’s player Alan Dennison was a servant of hell and whenever he played, the infernal instrument reverberated with the shrieks of the dead and the damned.” “Of course the police dismissed the paranormal connection,” Abbey said, taking her turn. “But the troupe didn’t have to be convinced. The fortune teller Madame Mori had seen the tragedy in her cards. Death. The Hanged Man. The Eight of Swords. Soon this land, next to Indiana’s cornfields, was all splattered with blood.” “Alan didn’t see it coming, despite the arguments he’d had with George over the noise. Then the ice pick was in his neck. Alan’s lover Dolores the Clown tried to stop him. All she got for her trouble was an instant lobotomy when he stabbed her in the eye.” “George poured kerosene over the bodies slumped against the tractor tow that pulled and powered the calliope then flicked the smoldering nub of his cigar to set it all ablaze. Next he pulled out his .22 pistol.” Abbey made a gun shape with her hand, “and blammo, he blew his fucking brains out.” Sara finished it up. “Soon the whole camp was gathered around the fire. The tattooed lady and the merman pulled Dolores to safety. She was alive, but burned, and never recovered her faculties. She spent the rest of her life at the Fort Wayne Sanitarium.” She let out her breath. “Legend has it, that if you come here and circle these ruins three times while reciting this chant, you can still hear Alan playing his calliope.” Sara and Abbey walked around, chanted, hands held. “See the freaks in a snow-white tent, See the tiger and elephant, See the monkey jump the rope, Listen to the Kally-ope! Hail, all hail, the cotton candy stand Hail, all hail, the steam whistle band. Music from the Earth am I! Circus days tremendous cry! My steam may be gone, But my sound will never die!” They chanted as they walked, and the late fall leaves crunched beneath their sneakers. Peggy saw a flicker of red and blue through the camera lens, then a painted face smeared with tears in the haze of moonlight and billows of steam. She smelled sulfur as an acrid taste crept into her mouth, and felt a weakness in the knees, as if she’d seen a guy she had crushed on, but now knew he was a creep, a sociopath hiding behind a charmed smile. She glanced at the ghostmeter clipped to the belt of her jeans and the numbers on its LED display jumped up and down. As they finished a third revolution around the circle, the ether blue outline of a faded canvas tent appeared with a whoosh of scorching vapor as the calliope released its high-pitched cry. A whirling gyre of phantasmal and miasmic shades slithered into being, spinning, as if on a carousel of sound, whose piercing tones splintered the air in a babble of laughter. Then it was gone, and only the smell of popcorn and sawdust remained. Sara felt sick to her stomach, and wished she hadn’t ordered the fried pickles at Diane’s Diner. As they walked back to the car, she couldn’t shake the high-pitched buzzing that rang and rang and rang in her ears, following her the whole way home.

0 Comments

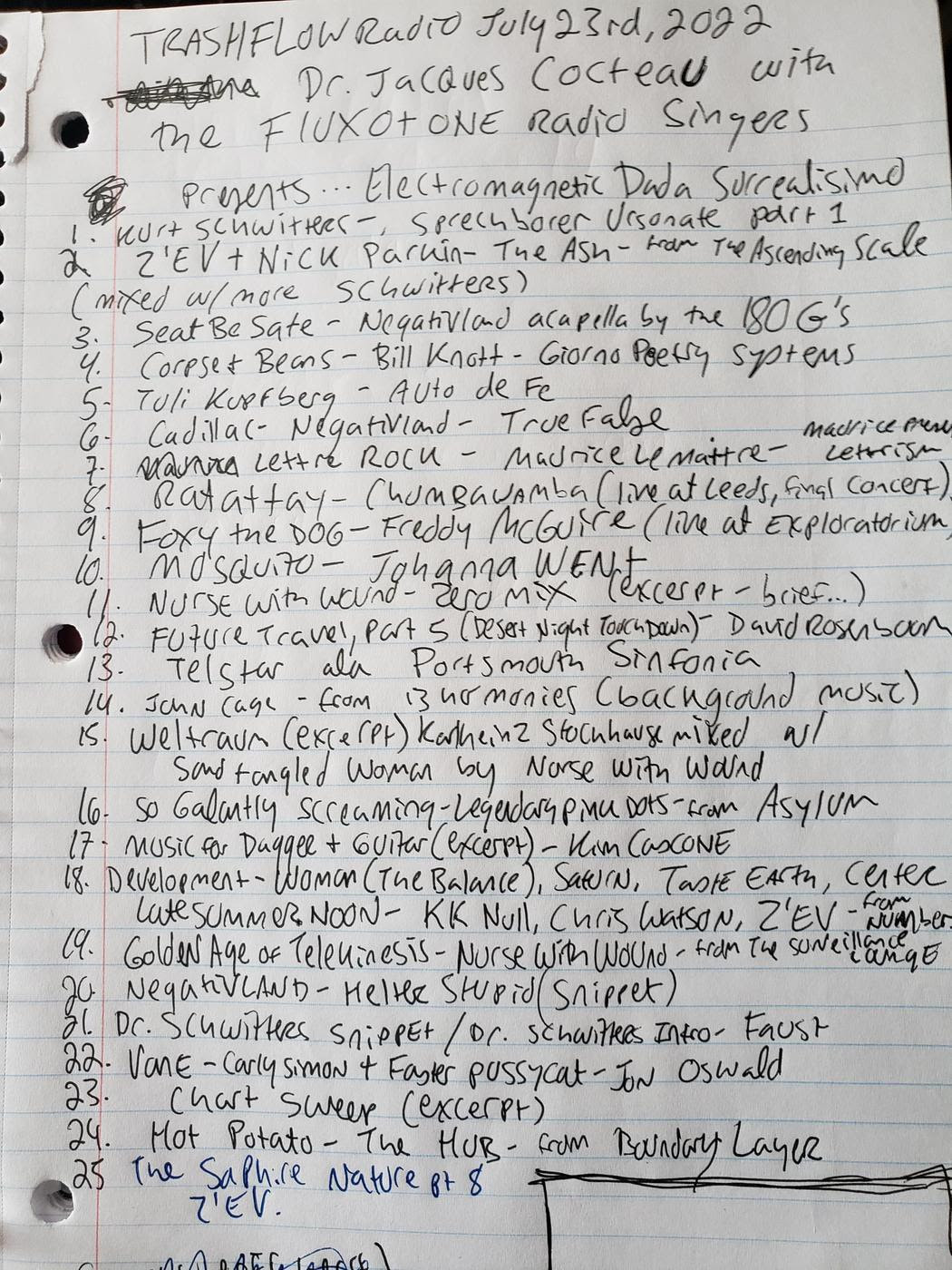

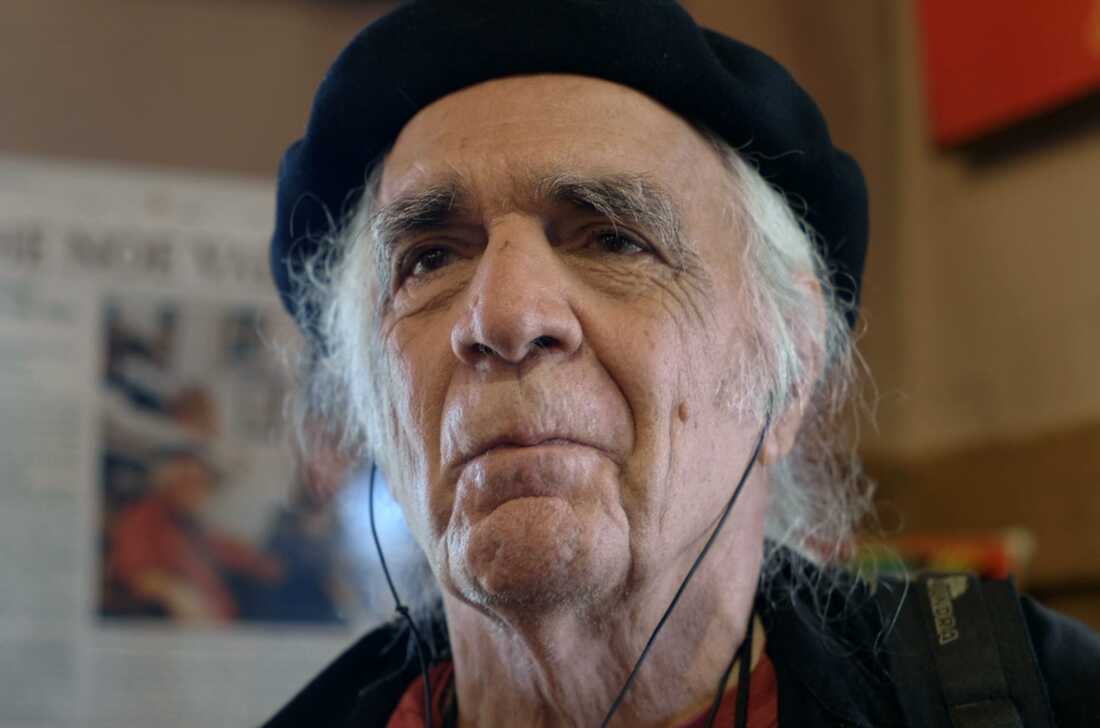

This selected Z'ev discography is included here to coincide with my article "Stream Foraging: Mudlarking for Found Objects and the Genius Loci" in my Cheap Thrills column out in in Vol. 2 Issue 3. of New Maps. The Z'ev section of the article focuses on his use of found objects in his music, with a special emphasis on his work creating sculptures out of materials found while mudlarking the River Thames. Z'EV was an American poet, percussionist, sound & visual/video artist. He studied a variety of world music traditions at CalArts. He was also extremely interested in using the drum, not just as a tool for musical entertainment, but communication and majik. He began creating his own percussion sounds out of industrial materials for a variety of record labels was considered pioneer of industrial music. Z'ev was a lifelong seeker. He was on a personal and poetic spiritual quest for knowledge and wisdom. He left traces of his quest behind in the form of the many artifacts, recordings, and texts he composed. The following list only scratches the surface of the various media he was able to create. A Selected Z’ev Discography: Z’ev. Elemental music. Subterranean Records, sub30, 1982, LP. Z’ev. My favorite things. Subterranean Records, sub33, 1985, LP. Genesis P-Orridge and Z’ev. Direction ov Travel. Cold Spring. CSR30CD. Originally released 1990 on Temple Records as Psychic TV, Direction ov Travel. (TOPY 059) Z'ev. Opus 3. Recorded at the church "De Duif", Amsterdam, April 20, 1990. Staalplaat. Z’ev. The Subterranean Years. Klanggalerie, gg129. 2009, compact disc. This recording is a reissue of Elemental Music and My Favorite Things on one CD. Z’ev. Face the Wound. Soleilmoon Records, Sol 72, 2001, compact disc. This album keeps with Z’ev’s aesthetic use of found materials, but here the materials are all recycled and sound collaged spoken word recordings found on tapes he collected scouring thrift stores and other second hand sources. The voices are foregrounded with the percussion as more of an accompaniment. Z’ev. The Sapphire Nature. Tzadik, TZ7161, 2002, compact disc. This recording taps into Z’ev’s cabalistic studies, and comprises “sixteen metaphonic meditations” on the Sefer Yetzirah or Book of Formation. The CD contains PDF material including a translation of the Sefer Yetzirah as well as essays and commentary by Z’ev. Z’ev, Parkin, Nick. The Ascending Scale. Soleilmoon Records, Sol 174, compact disc. Recorded in the Christ Church Crypt in Spitalfields, London. Christ Church was designed by architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, and built between 1714 and 1729. It has been considered an important location among psychogeographers, such as Iain Sinclair, as discussed in his book Lud Heat, and by other authors in other places. A variety of recordings, including many live performances, can be found here: https://zev-rhythmajik.bandcamp.com/ His book Rhythmajik: Practical Uses of Number, Rhythm and Sound, is available from archive.org. "Rhythmajik is not about music but spells out the use of rhythm and sound and proportion for Trance, Healing, etc. it features a unique Numerical Encyclopedia and two Numerical dictionaries comprising over 5000 beat patterns with their semantic meanings encompassing both healing and ritual vocabularies RHYTHMAJIK illuminates the processes allowing these vocabularies to be transformed into potent rhythmic patterns enabling you to focus the awesome energies of the Earth and Mother Nature and let them flow throughout and then out through you it includes information and has applications for people interested in Astrology, Divination, the Music of the Spheres, Numerology, Tarot and Visualization regardless of any particular interest in drumming and by the way, for the first time it delivers the functions of the 9 Chambers all that RHYTHMAJIK requires is the ability to count and the desire to achieve an intentionally considerate consciousness." .:. .:. .:. ELECTROMAGNETIC DADA SURREALISIMO on Trash Flow Radio with Dr. Jacques Cocteau and the Fluxotone Radio Singers Also in conjunction with the article "Stream Foraging: Mudlarking for Found Objects and the Genius Loci" in my Cheap Thrills column for Vol. 2 Issue 3. of New Maps, Dr. Jacques Cocteau put together this two hour radio special on the occasion of filling in for Ken Katkin on Trash Flow Radio. In this episode many recordings from Z'ev were featured, as well as Kurt Schwitter's related material.

Thanks to Ken for hosting the following on his extensive Trash Flow Radio Archive: Stream: Trash Flow Radio July 23, 2022 (Electromagnetic Dada Surrealisimo Special) (115 mins): <https://www.mixcloud.com/ken-katkin/trash-flow-radio-july-23-2022-electromagnetic-dada-surrealisimo/>. Download: Trash Flow Radio July 23, 2022 (Electromagnetic Dada Surrealisimo Special) (115 mins | 104 MB): <https://www.sendspace.com/pro/dl/dokaok>. Playlist For Trash Flow Radio -- July 23, 2022 (Electromagnetic Dada Surrealisimo Special): <https://imgur.com/UVPzoEq>. Sferics is one of Lucier’s most elegant and simple works. It is just a recording. Other versions of Sferics could be produced, and many science and radio hobbyists make similar recordings without ever having heard of Alvin Lucier. The phenomenon at the heart of Sferics existed long before they were ever able to be detected and recorded. Listening to this form of natural radio requires going down to the Very Low Frequency (VLF) portion of the radio spectrum.

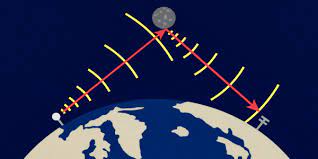

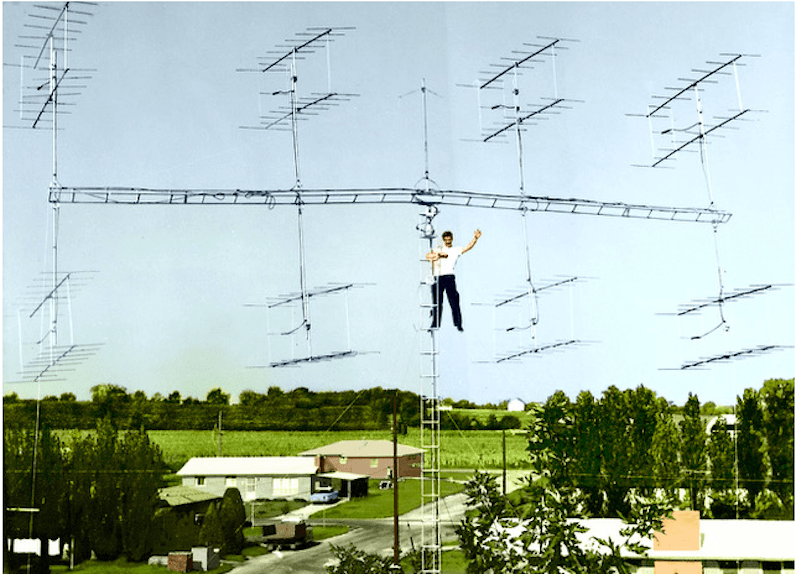

The title of Lucier’s work refers to broadband electromagnetic impulses that occur as a result of natural atmospheric lightning discharges and are able to be picked up as natural radiofrequency emissions. Listening to these atmospherics dates all the way back to Thomas Watson, assistant of Alexander Graham Bell, as mentioned at the beginning of this book. He picked them up on the long telegraph lines which acted as VLF antennas. Since his time telegraph operators and radio hobbyists and technicians have heard these sounds coming in over their equipment. For some chasing after these sferics has become a hobby in itself. The VLF band ranges from about 3 kHz to 30 kHz and the wavelengths at this frequency are huge. Most commercial ham radio transceivers tend to only go as low as 160 meters which translates to between 1.8 and 2 MHz in frequency. A VLF wave at 3 kHz is by comparison a length of 100 kilometers. The VLF range includes a portion of the spectrum that is in the range of human hearing, from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. Yet since the sferics are electromagnetic waves rather than sound waves a person needs radio ears to listen to them: i.e., an antenna and receiver. On average lightning bolts strike about forty-four times a second, adding up to around 1.4 billion flashes a year. It’s a good thing the weather acts as a variable distribution system of these strikes, though some places get hit more than others. The discharge of all this electricity means there are a lot of electromagnetic emissions from these strikes going straight into the VLF band where they can be listened to with the right equipment. Because these wavelengths are so long, you could be in California listening to a thunderstorm in Italy or India, or in Maine listening to sferics caused by storms in Australia. The sound of sferics is kind of soothing and reminds me of the crackle of old vinyl that has been unearthed from a dusty vault in a thriftstores basement. There are lots of pops and lots of hiss. As these are natural sounds picked up with the new extensions to our nervous system made available by telecommunications listening to sferics has the same kind of soothing effect as listening to a field recording of an ocean, or stream meandering through lonely woods. But for a long time, listeners, hobbyists and scientists didn’t really know what these emissions were caused by. During the scientific research activities surrounding the International Geophysical Year (IGY) overlapping 1957-58 their presence and source was verified. The IGY yearlong event was an international scientific project that managed to receive backing from sixty-seven countries in the East and West despite the ongoing tensions of the Cold War. The focus of the projects was on earth science. Scientists looked into phenomena surrounding the aurora borealis, geomagnetism, ionospheric physics, meteorology, oceanography, seismology, and solar activity. This was an auspicious area of study for the scientists, as the timing of the IGY coincided with the peak of solar cycle 19. When a solar cycle is at its peak, the ionosphere is highly charged by the sun making radio communications easier, and producing more occurrences of aurora, among other natural wonders. One of the researchers was a man by the name of Morgan G. Millett, and his recordings would go on to have a direct influence on Alvin Lucier. Millet was an astrophysicist who had established one of the first programs to use the fresh discoveries occurring in the VLF band as a way to investigate the properties of space plasma around the earth, in the region now known as the upper ionosphere and magnetosphere. His inquiries into this area allowed for deep gains of knowledge in a new area of study before space-crafts began making direct observations of this area. Millet was also a ham radio operator with the call sign W1HDA. He had been interested in radio since he was a teenager, and throughout his career found ways to use his inclination and knack to research propagation. Throughout the 1940s and early 50s Millet and his colleagues conducted radar experiments near his home in Hanover, New Hampshire. The purpose of these studies was to observe two modes of propagation that magnetoionic theories had predicted would occur when radio waves entered the atmosphere. During the IGY he chaired the US National Committee's Panel on Ionospheric Research of the National Research Council. In this capacity he oversaw the radio studies being conducted all around the earth. As part of that work he joined the re-supply mission to the US Antarctic station on the Weddell Sea in early 1958 as the senior scientific representative. For his own specific research he maintained a series of far-flung stations spread across the Americas. It was from these that he made a number of recordings of natural radio signals. Lucier later heard these at Brandeis. The composer writes, “My interest in sferics goes back to 1967, when I discovered in the Brandeis University Library a disc recording of ionospheric sounds by astrophysicist Millett Morgan of Dartmouth College. I experimented with this material, processing it in various ways -- filtering, narrow band amplifying and phase-shifting -- but I was unhappy with the idea of altering natural sounds and uneasy about using someone else's material for my own purposes.” Millets recordings were made at a network of receiving stations and he interpreted the audio data he collected to obtain some of the earliest measurements of free electron density in the thousands of kilometers above earth. A colorful vocabulary was built up to describe the sounds heard in the VLF portion of the spectrum. Sferics that traveled over 2,000 kilometers often shifted their tone and came to be called tweeks; the frequency would become offset as it traveled in distance, cutting off some of the sound and making it sound higher in the treble range. Whistlers were another phenomenon heard on the air. They occurred when a lightning strike propagated out of the ionosphere and into the magnetosphere, along geomagnetic lines of force. The sound of a whistler is one of a descending tone, like a whistle fading into the background, hence its name. It is similar to the tweek, but elongated due to it stretching out away from the surface followed by a return to the Earth’s magnetic field. Dawn chorus is another atmospheric effect some lucky eavesdroppers in the VLF range may be able to pick up from time to time. It is an electromagnetic effect that may be picked up locally at dawn. The cause of this is thought to be generated from energetic electrons being injected into the inner magnetosphere, something that occurs more frequently during magnetic storms. These electrons interact with the normal ambient background noise heard in the VLF band to create a sound that is actually similar to that of birdsong in the morning. This sound is likely to be heard when aurorae are active when it is dubbed auroral chorus. Millets experimental work in recording these phenomena created a foundation to study such things as how the earth and its magnetic field interact with the solar wind. Listening to Millet’s recordings wasn’t enough for Lucier. “I wanted to have the experience of listening to these sounds in real time and collecting them for myself. When Pauline Oliveros invited me to visit the music department at the University of California at San Diego a year later, I proposed a whistler recording project. Despite two weeks of extending antenna wire across most of the La Jolla landscape and wrestling with homemade battery-operated radio receivers, Pauline and I had nothing to show for our efforts. . . .” The idea was shelved for over a decade. In 1981 Lucier tried again. He got a hold of some better equipment and was able to go out to a location in Church Park, Colorado, on August 27th, 1981. For the Colorado recording he collected material continuously from midnight to dawn with a pair of homemade antennas and a stereo cassette tape recorder. He repositioned the antennas at regular intervals to explore the directivity of the propagated signals and to shift the stereo field. This was all done at Church Park, August 27th, 1981. It was in the early 80s that Millet continued his own radio investigations. He built a network of radar observing stations to study gravity waves that propagate to lower latitudes of Earth from the arctic region. These gravity waves appear as propagating undulations in the lower layers of the ionosphere. Lucier wasn’t the only musician to be interested in this phenomenon. Electronic music producer Jack Dangers explored these sounds under his moniker as Meat Beat Manifesto on a song called The Tweek from the album Actual Sounds & Voices. Pink Floyd used dawn chorus on the opening track of their 1994 album the Division Bell. VLF enthusiast Stephen P. McGreevy has been tracking these sounds for some time, and has collected a lot of recordings and been releasing them on CD and the internet via archive.org. At the time of this writing he has made eight albums of such recordings. On the communications side of things the VLF band’s interesting properties have been exploited for use in submarine communication. VLF waves can penetrate sea water to some degree, whereas most other radio waves are reflected off the water. This has allowed for low-bitrate communications across the VLF band by the worlds militaries. Some hams have also taken up experimenting with communication across VLF, learning more about its unique propagation in doing so. Just as the Hub was getting off the ground and into circulation as a performing ensemble, one of its members, Scott Gresham-Lancaster, was working with Pauline Oliveros on a new project she had initiated in creating the ultimate delay system: bouncing her music off the surface of the moon and back to earth with the help of an amateur radio operator. Since Pauline had first started working with tape she had always been interested in delay systems. Later she started exploring the natural delays and reverberations found in places such as caves, silos and the fourteen-foot cistern at the abandoned Fort Worden in Washington state. The resonant space at Fort Worden in particular had been important in the evolution of Pauline’s sound. It was there she descended the ladder with fellow musicians Paniotis, a vocalist, and with trombonist Stuart Dempster to record what would become her Deep Listening album. Supported by reinforced concrete pillars the delay time in the cistern was 45 seconds, creating a natural acoustic effect of great warmth and beauty. This space continued to be used by musicians, including Stuart Dempster, and the place was dubbed by them, the cistern chapel. Pauline had another deep listening experience in a cistern in Cologne when visiting Germany. Between these experiences, the creation of the album, and the workshops she was starting to teach, she came up with a whole suite of practices and teachings that came to be called Deep Listening. The term itself had started as a pun when they emerged up from the ladder that had taken them into the cistern. Pauline describes Deep Listening as, “an aesthetic based upon principles of improvisation, electronic music, ritual, teaching and meditation. This aesthetic is designed to inspire both trained and untrained performers to practice the art of listening and responding to environmental conditions in solo and ensemble situations.” Since her passing Deep Listening continues to be taught at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute under the directorship of Stephanie Loveless. The idea of bouncing a signal off the moon, which amateur radio operators had learned to do as a highly specialized communications technique, was another way of exploring echoes and delays, in combination with technology in a poetic manner. Pauline first had the idea for the piece when watching the lunar landing in 1969. “I thought that it would be interesting and poetic for people to experience an installation where they could send the sound of their voices to the moon and hear the echo come back to earth. They would be vocal astronauts. My first experience of Echoes From the Moon was in New Lebanon, Maine with Ham Radio Operator Dave Olean. He was one of the first HROs to participate in the Moon Bounce project in the 1970s. He sent Morse Code to the moon and got it back. This project allowed operators to increase the range of their broadcast. I traveled to Maine to work with Dave. He had an array of twenty four Yagi antennae which could be aimed at the moon. The moon is in constant motion and has to be tracked by the moving antenna. The antenna has to be large enough to receive the returning signal from the moon. Conditions are constantly changing - sometimes the signal is lost as the moon moves out of range and has to be found again. Sometimes the signal going to the moon gets lost in galactic noise. I sent my first ‘hello’ to the moon from Dave's studio in 1987. I stepped on a foot switch to change the antenna from sending to receiving mode and in 2 and 1/2 seconds heard the return ‘hello’ from the moon.” Though farther away in space than the walls of the worden cistern, the delay time between the radio signal going there and coming back is much shorter. In a vacuum radio waves travel at the speed of the light. Earth Moon Earth, or EME as it is known in ham radio circles was first proposed by W. J. Bray, a communications engineer who worked for Britain’s General Post Office in 1940. At the time, they thought that using the moon as a passive communications satellite could be accomplished through the use of radios in the microwave range of the spectrum. During the forties the Germans were experimenting with different equipment and techniques and realized radar signals could be bounced off the moon. The German’s developed a system known as the Wurzmann and carried out successful moon bounce experiments in 1943. Working in parallel was the American military and a group of researchers led by Hungarian physicist Zoltan Bay. At Fort Monmouth in New Jersey in January of 1946 John D. Hewitt working with Project Diana carried out the second successful transmission of radar signals bounced off the moon. Project Diana also marked the birth of radar astronomy, a technique that was used to map the surfaces of the planet Venus and other nearby celestial objects. A month later Zoltan Bay’s team also achieved a successful moon bounce communication. These successful efforts led to the establishment of the Communication Moon Relay Project, also known as Operation Moon Bounce by the United States Navy. At the time there were no artificial communication satellites. The Navy was able to use the moon as a link for the practical purpose of sending radio teletype between the base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, to the headquarters at Washington, D.C. This offered a vast improvement over HF communications which required the cooperation of the ionospheric conditions affecting propagation. When the artificial communication satellites started being launched into orbit the need to use the moon for communicating between distant points was no longer necessary. Dedicated military satellites had an extra layer of security on the channels they operated on. Yet for amateur radio operators the allure of the moon was just beginning, and hams started using it in the 1960s to talk to each other. It became one of Bob Heil’s favorite activities. In the early days of EME hams used slow-speed CW (Morse Code) and large arrays of antennas with their transmitters amplified to powers of 1 kilowatt or more. Moonbounce is typically done in the VHF, UHF and GHz ranges of the radio spectrum. These have proven to be more practical and efficient than the shortwave portions of the spectrum. New modulation methods also have given hams a continuing advantage on using EME to make contacts with each other. It is now possible using digital modes to bounce a signal off the moon with a set up that is much less expensive than the large dishes and amounts of power required when this aspect of the hobby was just getting started.

“For instance, an 80W 70 cm (432 MHz) setup using about a 12-15 dBi Yagi works well for EME Moonbounce communication using digital modes like the JT65,” writes Basu Bhattacharya, VU2NSB, a ham and moonbouncer located in New Delhi, India. On the way to the moon and back, the radio path totals some 50,000 miles and the signals are affected by a number of different factors. The Doppler shift caused by the motion of the moon in relation us surface dwellers is an important factor for making EME contacts. It is also something that effected the sound of the Pauline’s music when it got bounced off the lunar surface. “The sound shifted slightly downward in pitch… like the whistle of a train as it rushes past,” said Pauline of her performance. “I played a duo with the moon using a tin whistle, accordion and conch shell. I am indebted to Scott Gresham-Lancaster who located Dave Olean for me in 1986 and helped to determine the technology necessary to perform Echoes From the Moon. Ten years later Scott located all the Ham Radio Operators for the performance in Hayward, California which took place during the lunar eclipse September 23, 1996. Following is the description of that performance: The lunar eclipse from the Hayward Amphitheater was gorgeous. The night was clear and she rose above the trees an orange mistiness. As she climbed the sky the bright sliver emerged slowly from the black shadow - crystal clear. The moon was performing well for all to see. Now we were ready to sound the moon. “The set up for Echoes From the Moon involved Mark Gummer - a Ham Radio Operator in Syracuse New York. Mark was standing by with a 48 foot dish in his back yard. I sent sounds from my microphone via telephone line in Hayward California to Mark and he keyed them to the moon with his Ham Radio rig and dish and then he returned the echo from the moon. The return came in 2 & 1/2 seconds. Scott Gresham-Lancaster was the engineer and organized all. When the echo of each sound I made returned to the audience in the Hayward University Amphitheater they cheered. Later in the evening Scott set up the installation so that people could queue up to talk to the moon using a telephone. There was a long line of people of all ages from the audience who participated. People seemed to get a big kick out of hearing their voices return - processed by the moon. There is a slight Doppler shift on the echo because of the motion of both earth and moon. This performance marked the premiere of the installation - Echoes From the Moon as I originally intended. The set up for the installation involved Don Roberts - Ham Radio Operator near Seattle and Mike Cousins at Stanford Research Institute in Palo Alto California. The dish at SRI is 150 feet in diameter and was used to receive the echoes after Don keyed them to the moon. With these set ups it was only possible to send short phrases of 3-4 seconds. The goal for the next installations would be to have continuous feeds for sending and receiving so that it would be possible to play with the moon as a delay line.” It's a set up that could work for other musicians who want to realize again Oliveros’s lunar delay system. Or it could be modified to create new works. The thrill of hearing a sound or signal come back from the moon remains, and if creative individuals get together to explore what can be done with music and technology, new vistas of exploration will open up. .:. .:. .:. Read the rest of the Radiophonic Laboratory: Telecommunications, Electronic Music, and the Voice of the Ether. RE/Sources: http://www.kunstradio.at/VR_TON/texte/4.html https://muse.jhu.edu/article/810823 Furniture Music Over the course of the 20th century a music concerned with various aspects of space and spatialization began to take shape. It was a music with its roots in both the aether and the living room, this latter because of the influence of Erik Satie. Satie was to have many influences on musical developments after him. One stream was the noisy yet minimalist vein that came from the influence of his piece Vexations. The other was as the spiritual god father of ambient, descending from his conceptions of Furniture Music. This latter is what concerns us here. In French the term is musique d’ameublement a phrase he coined in 1917 and is generally taken to mean background music. It’s literal translation is furnishing music, though in English it has been standard to call it furniture music. It was a breakthrough idea in western music as it the music itself was to be a part of the room, a sonic background to furnish the space and not intended as something that needed to be directly focused on. Many of Satie’s pieces can be experienced as furniture music, but he only gave the name to five short pieces. The names are often indicative of how the music relates to a specific space. Satie had a notion of music that could "mingle with the sound of the knives and forks at dinner." His first set of furniture pieces gave that notion a form. The first set of furniture music he wrote has names like “Tapisserie en fer forgé – pour l'arrivée des invités (grande réception) – À jouer dans un vestibule – Mouvement: Très riche (Tapestry in forged iron – for the arrival of the guests (grand reception) – to be played in a vestibule – Movement: Very rich)” and “Carrelage phonique – Peut se jouer à un lunch ou à un contrat de mariage – Mouvement: Ordinaire (Phonic tiling – Can be played during a lunch or civil marriage – Movement: Ordinary)” The second set was composed as intermission music for a comedy by Max Jacob that has since been lost. As intermission music the idea of background ambience to fill the space is again asserted. Not much else was done with the furniture music and it remained largely unknown to the public except for being mentioned in a few biographies of the composer. In the 1960s some facsimiles of his scores appeared in the then new biographies coming out on Satie, with publication of the scores following in the 70s. In America Satie’s ideas and music found a champion in John Cage. Cage was stimulated by the idea of furniture music and it inspired his own experiments and theories for a minimalist background music. Furniture music became a nucleus around which the minimalist and avant-garde composers rallied around with its emphasis on being played not as the centerpiece, but as something to create a space which people lived and moved inside of. Atmosphere, timbre, texture, long durations, repetition, and drone a part of the milieu. These tendencies towards texture and drone were picked up by Brian Eno who built upon the idea of furniture music on his album Discreet Music (discussed in terms of its relation to cybernetics and information theory in Chapter 3). Eno thought of Discreet Music, as just what one of the definitions of the word discreet means: unobtrusive and unnoticeable. ''The ambient records are similar to paintings,'' Eno says. ''You don't gaze at a painting for hours each day. But you're aware of its presence, and occasionally you choose to go into it deeply - at a time when you're receptive and want it to affect your mood.'' The minimalist and ambient aspects of furniture music built on by Cage and Eno became major strands of what was to become Space Music. Another major strand came again from that great force of nature, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and the German electronic musicians who followed his lead starting in the 1960s and 70s. The Spatialization of Space At the WDR Stockhausen became a colleague of Robert Beyer in 1953 (see Chapter 5). In a 1928 paper Beyer wrote about “Raummusik” or spatial music. It wasn’t about music from the stars, or music to create an atmosphere in a specific space as Satie had done with his furniture pieces, but was focused on the possibilities of having different sound elements localized at specific points within a concert hall or listening space. With the advent of electroacoustic music the spatialization of sound also became about certain sounds being in specific loudspeakers and moving sounds from one loudspeaker to another within a system. Stockhausen took the idea of spatial music, and the term, and ran with it, with composed spatial elements running throughout many of his works. And while this spatial element was very dear to Stockhausen, he was also interested in creating music inspired by outer space and the greater cosmos. Following a performance of Hymnen in 1967 he said, “Many listeners have projected that strange new music which they experienced—especially in the realm of electronic music—into extraterrestrial space. Even though they are not familiar with it through human experience, they identify it with the fantastic dream world. Several have commented that my electronic music sounds ‘like on a different star,’ or ‘like in outer space.’ Many have said that when hearing this music, they have sensations as if flying at an infinitely high speed, and then again, as if immobile in an immense space. Thus, extreme words are employed to describe such experience, which are not ‘objectively’ communicable in the sense of an object description, but rather which exist in the subjective fantasy and which are projected into the extraterrestrial space." Many of Stockhausen’s pieces of music are concerned with outer space, the constellations, and stars. It was a recurrent theme throughout the compositions he wrote in the 1970s, and he spiraled back to space and the stars again and again throughout his creative life. As such a few of the relevant pieces will be explored here and others will be examined in more depth in their own sections of this chapter. Sternklang is a piece of music that pulls together Stockhausen’s interest in combinatorial systems (Glass Bead Games), spatial music, and intuitive music, among other things. "park music", to be performed outdoors at night by 21 singers and/or instrumentalists divided into five groups, at widely separated locations. In a park at night the sky is open to all who want to receive the light and blessing of the stars, of those things coming into being. In the score Stockhausen says simply that the music is sacred and that it is best performed on in the warmth of summer on when the moon is full. Stockhausen says of the piece, “STERNKLANG is music for concentrated listening in meditation, for the sinking of the individual into the cosmic whole”. The music itself bears many similarities to Stimmung, in that overtone singing is done by the vocalists based on various combinations of vowel phonetics. The instrumentalists are also required to create overtones and also use synthesizers, sometimes processing their sound through the synth to create the required overtones. The groups are spaced approximately 60 meters apart from each other, creating the spatial effects for listeners who are wondering around the park, stopping here and there to listen to the different ways the music sounds in separate but overlapping spaces. Loudspeakers amplify the different groups, and each group is supposed to be situated that they can hear at least one or two other groups. These separate groups of players perform independently of one another, but they also synchronize together at ten different times during the performance. The synchronization is done through the work of the torch-bearers and sound-runners. They run from one group to another, the torch bearer lighting the way, the sound runner, giving a musical “model” to the other groups. In the center of the park a percussionist synchronizes the musicians to a common tempo. This complex work has an equally complex score, made up of a text illustrating the concept, a Formscheme, five pages each with six of the Models to be played in a variety of combinations, ten pages with ten Special Models, and a page of Constellations. All this material is given to the different groups of musicians who use parts of it for the structure according to the instructions. From this material many completely different performances of Sternklang could be given, due to the combinatorial aspect. Yet they would all sound consistent as Sternklang. The score is a vessel into which the musical energies are poured, and though the contents may differ between performances, the vessel itself lends its form. The Special Models are the only times when the five groups are synchronized via the tam-tam, yet even within these there are part-patterns that may differ. Mixed in at different points of the music are the Constellations. These points are based on the actual constellation shapes interpreted as relative pitch and loudness. Meanwhile, the thirty different Models give instruction for how to sing the pitch material using the phonetic vowels from the constellation names so as to accentuate the overtones. Just as in Stimmung, the names are considered to be ones full of magical power. In all the overtones played there is a unique oscillation, created by the mouth by the vocalists, while the synthesizer players use timbre filters, and the trombone players use mutes. The five different groups can be conceived as their own constellations, at times vibrating with their own rhythms, songs, tones. At other times they come into synchronized harmony. Drifting about these constellations are the human listeners, being exposed at different points to the intense and pure musical light of the star sounds. He followed up Sternklang with Ylem, Tierkreis and Sirius. When Licht took over his compositional life starting in 1977 he managed to continue to work in themes of space, and worked dizzying amounts of spatialization and sound projection techniques into the various pieces that make up his magnum opus. Of these the pieces Weltraum (Outer Space, 1991–92/1994), Komet (Comet, 1994/1999), Lichter—Wasser (Lights—Waters, 1998–99) are especially significant. Michaelion (1997) is likewise discussed (at the end of the chapter or in the section on shortwave radio). In the Klang cycle his final series of works, he continued to be inspired by the stars. The electronic chamber piece Cosmic Pulses sees him completely leave the orbit of previous Earth music’s in his spatial exploration of space. Stockhausen’s influence fed more or less directly into the Kosmiche genre of music in Germany starting in the late 1960s. Other Planes of There If you’ve ever listened to the music of Sun Ra you know that space is the place. To say that Sun Ra was interested in space music from a cosmic perspective is an understatement. The man from Saturn himself said "When I say space music, I'm dealing with the void, because that is of space too... So I leave the word space open, like space is supposed to be." In the 1930s when Herman Blount was taking a training course to become a teacher in Huntsville, Alabama, he received some visitors who established his true calling. He was to be a teacher, but not a school teacher. These visitors, Blount said, were aliens, who had antennas that grew above their eyes and on their ears, perhaps attuned to the wavelengths of cosmic music. They transported Sonny Blount, and this transportation caused him to metamorphosize into Sun Ra, after his visit to the planet Saturn. There he was given a set of metaphysical equations that surpassed the trivial knowledge of Earth. At the proper time, these beings told him, when life on Earth was filled with despair, he could set out to teach humanity. The vehicle for his teaching was music, and his message was one of discipline. This experience informed Ra's work for the rest of his life. It changed him on a fundamental level, and from it he continued his quest into music and metaphysics. Sun Ra steeped himself in mystic lore. His birth name came from Black Herman, the stage name of stage magician, hoodoo practitioner, and seller of patent medicines. His act was mixed the illusions of being "buried alive" and other escapes and that of a traveling medicine show catering to African-Americans. Black Herman was the author of Secrets of Magic, Mystery, and Legerdemain, that contained a mythologized biography, and a selection of material on sleight of hand, hoodoo folk magic, astrology, lucky numbers, dreams and more. The name Herman itself calls to mind that trickster and communicator Hermes, though it's etymology is actually German from the words harja- "army" and mann- "man". Though Herman Blount changed his name, in many ways he followed in the footsteps of his namesake, and lived a life of magic and mystery. Like Black Herman he created a mythology around his life that became part of his teaching vehicle, just as his music became a vehicle for space travel. Ra's band was not a band. They were a group of "tone scientists". They weren’t an orchestra, they were an arkestra, and their music was a way to travel the outerspace ways, and to bring the sounds of the cosmos down hear onto Earth. The way Ra’s compositions swing, showed that they weren’t tied to the gravity well of our planet, but orbited around vast interplanetary spheres. For all the free-wheeling moments of parts of the Sun Ra's ouvre, it came from his total discipline. His music sounds wild, out there, but it came from his total devotion to music. He abstained from alcohol, and encouraged his band members to do the same. He abstained from sex, drugs, and even sleep. The rock and roll ethos was his antithesis. For him there was sanctity to his calling as a musician, tied up as it was with also being a messenger from another world. His band practiced for hours and hours, in the middle of the night when Ra couldn’t sleep, late in the afternoon when he was jolted out of a brief catnap, in the morning when they no longer remembered what day it was, they were playing music. It was always in their mind and they were ready to swing. Sun Ran and his Arkestra were so prolific it is beyond the scope of this section to go into the vast penumbra that is his legacy and work. The theme of space reverberates throughout his records. So were the sounds of the space age. Sun Ra was one of the first jazz musicians, if not the first, to get into the synthesizer game, bringing the sound of the Minimoog into his already swirling cosmic pallette. Sun Ra believed it was important for black musicians to get into the world of electronic music, to start exploring the experimental sounds of the space age made possible by technology. For the makers of synthesizers, Jazz was a genre where they had yet to have a presence. All that changed between 1969 and 1970 when Sun Ra was invited to visit the Moog workshop in Trumansburg, NY. As one of the great jazz pianists Sun Ra had already availed himself of the electric sounds that became available in the 50s and 60s. These included electric piano, electric Celeste, Hammond organ, and the Clavioline. The Clavioline was memorably used on Joe Meek's production of Telstar by the Tornadoes. It was a vacuum tube based monophonic keyboard that gave an otherworldly vibe to many songs. Sun Ra loved the expanded timbre palette these keyboard instruments gave his voracious appetite for sound and he was always looking for what else might come down the line, and the Moog was his ticket into the seventies. Sun Ra had met Robert Moog when a journalist at the jazz rag Downbeat arranged for Sun Ra to visit the Moog factory. Sun Ra got a chance to got his expert hands on the Minimoog which was still in pre-production. The great synthesizer maker even gave the great Ra a prototype to take back with him. At the time the portable synthesizer was just an idea. The synths at the time were messy affairs taking up rooms and patched with huge amounts of cables. While the results of these instruments switched on many to their well-tempered sounds, as a touring instrument the Moog was untested, and its little brother the Minimoog was still in infancy. Sun Ra not only tested it's possibilities but took it out into the greater solar system on a scouting mission that brought space sounds into Sun Ra's live and recorded sessions. His track Space Probe, for example, was an extended solo with the Minimoog. As new keyboards found their way into the market they would often find their way to Sun Ra who continued to include such stalwarts as the Yamaha DX7 into his interplanetary musical concepts. From Kosmiche to Hearts of Space Kosmiche can be considered a synonym for Krautrock. The term was in use in Germany before the Krautrock label got thrown onto bands like Can (whose members Holger Czukay and Irmin Schmidt were students of Stockhausen), Ash Ra Temple, Faust and Guru Guru by the music press in England. Krautrock itself can be seen as a highly psychedelic vision of rock music with a heavy emphasis on synthesizers and propulsive motorik rhythms dressed with jazz improvisations and avant-garde tape editing techniques. It owed less to blues music, than rocks American and English counterparts, yet was indebted to the scenes of free improvisation happening in art music and jazz circles. A lot of it can be cosmic and spacey, but the extended synthesizer escapades of Popul Vuh, Amon Duul II, and especially Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulze all went on to put their stamp on the emergent genre of ambient space music that would be epitomized in the set lists of the of the radio show Hearts of Space. On Tangerine Dream’s 1971 album Alpha Centauri the music was described in the liner notes as “kosmiche musik”. Julian Cope noted that the album was like Pink Floyd’s Saucer Full of Secrets, but minus the rock. It spread further, when their record label, OHR, put out a compilation with the name as a title. These Germans had found inspiration in the range of sounds now available to them with the Moog Modular, and with the EMS VCS3. They were also eager to separate their sound from their troubled nations past, and focusing on outer space, at the height of the space race and optimism about humanities exploration of the cosmos, was one solution. Space rock continued as one vein of this music, and another more ambient strain continued to emerge from others who found inspiration from the star sounds of Alpha Centauri. Klaus Schulze was another heavy influence on this emergent sound. Before he began his prolific solo career he’d already been playing with Tangerine Dream on their first album Electronic Meditations, after which he left to form Ash Ra Temple, made one album with them and departed. He also played sessions with the acid soaked Cosmic Jokers. Once he went solo he truly flourished as an artist. His first solo album Irrlicht came out in 1972 and featured a modified electrical organ as the main sound source and samples of classical symphonic music played backwards and run through a messed up amplifier to transform the sounds, which he mixed to tape for a three-movement symphony. Cyborg was his next album, and featured a similar set up, while Timewind from 1975 saw his first use of a sequencer which became a staple of his process. The pieces here are sidelong masterpieces easy to lose a sense of time while listening to. It was in these same years that Stephen Hill founded his radio show Music from the Hearts of Space, originally on KPFA. He used the pseudonym Timmotheo, and when his co-host Ann Turner joined him, she used the on air alias Annamystic. In its original incarnation it was a three-hour long late night excursion into all things “space music”. Hill had been an architect by training, and he was interested in all kinds of contemplative music, and also music that could fill up a space. The kosmiche sounds coming out of Germany certainly fit the bill. The program grew to fill its own niche and encompassed a mix of a wide range of ambient, electronic, world, new age, classical and experimental music. Space music can act as an isolation chamber when skillfully constructed, and excels over an expanded range of time. Steve Roach and Robert Rich both got started in the late seventies with albums coming out in the early eighties. There complimentary styles were perfect for the further growth of ambient space music and the two artists became closely associated with the milieu of music presented on Hearts of Space. At the age of twenty when Steve Roach wasn't practicing to up his game as a Motocross racer, he was listening to the sounds of Vangelis, Klaus Schulze, and Tangerine Dream. After he suffered from a bike crash that led him into a near-death experience, where he heard "the most intensely beautiful music you could ever imagine" he reorganized his life and dedicated it to recreating the music he had heard. Out of this experience came his landmark and timeless album called "Structures from Silence." Roach has said that others who have had near-death experiences tell him that they heard similar music. He had acquired his first synthesizer about six years before the accident, in 1978 and taught himself to play, inspired by the music he'd been listening to. In 1982 his first album, Now, came out. Then the bike crash. From that time on his life has been devoted to bringing people music that communicates a spiritual perception of space and time, flow, at once in touch with the landscapes of the earth, as with the vast expanse of silence within the void. The three long tracks on Structures from Silence encapsulate the listener within a web of harmonic waves. From that release onwards Roach has been relentless in his mission to bring a music of space, stillness, and quiet noise into the hearts and heads of his many listeners. The music of Roach became a staple on Hearts of Space, and a bridge between the adjacent worlds of ambient and new age. Tribal soundworlds were also explored when Roach visited Australia. He fell in love with the desert outback and the didgeridoo. He learned to play the instrument, and started incorporating into his music. Roach was also studying the Aboriginal Dreamtime, and going on walkabouts in the desert of his of California. These influences came to the fore on his 1988 classic Dreamtime Return. The desert became a spiritual home for Roach, and he eventually moved to Arizona where the wide open landscape continues to be a source of inspiration. Out of these experiences, and collaborations with many artists, Roach helped to create the tribal ambient and tribal techno subgenres. Another artist in a similar vein, who has also collaborated with Roach, is Robert Rich, whose music is another frequent touchstone on Hearts of Space playlists. They also began their careers around the same time, with Rich releasing his first album Sunyata in 1982. Like Roach his signature soundworlds have helped to further define an organic and at times tribal strain of ambient. Rich also goes in for explorations into propulsive beat centered trance rhythms, with extensive explorations of alternate tuning systems, recalling the works of Terry Riley and Steve Reich, abetted with the help of a sequencer. Robert Rich also has a penchant for all night concerts, just as Riley did with his longform raga inspired minimalism, but Rich took his performances in a different direction, with quieter sounds. He used his sleep concerts as a vehicle for exploring the nature of sleep, consciousness and dreams. Hearts of Space founder Stephen Hill notes, “What's now being called Ambient music is the latest chapter in the contemplative music experience. Electronic instruments have created new expressive possibilities, but the coordinates of that expression remain the same. Space-creating sound is the medium. Moving, significant music is the goal.” Radio remains a perfect medium for presenting this type of music and Hill and Turner would do long hour long blocks with no voice interruptions as DJs until the end of each hour, when they would announce what they heard. This allowed the listeners to sink into the experience with being brought out of their contemplative reverie. In 1983 after ten years on KPFA Hearts of Space started to be syndicated on 35 National Public Radio stations around the United States via the Public Radio Satellite System. It continued into the era of net streaming and in 2009 it was still on two hundred public radio stations. It moved into orbit with Sirius XM for a time. On November 12, 2021, it reached its latest milestone, 1,300 installments. Earth Station One: John Shepherd Beamforms to Space