|

Reflections on Skinny Puppy, Bogarts April 28th, 2023 I never thought I’d get to see Skinny Puppy live. Back in 1999 when I first became a fan of the band, around the age of twenty, they had fallen into an inactive stasis. At that time their last album had been The Process. The album was marked by a number of production and recording issues that had largely been absent from the collaborative spirit felt by the members on previous albums and punctuated by the death of Dwayne Goettel. The band dissipated, but cEvin Key kept busy with his Download project. Download had been my first entry point towards Skinny Puppy anyways. The other entry point had been The Tear Garden. This group had been formed by cEvin Key with Edward Ka-Spel from the Legendary Pink Dots -still one of my favorite experiemental-psychedelic-goth bands ever. The Tear Garden featured a lot of other members from both Skinny Puppy and Legendary Pink Dots, and I was obsessed with the Dots and Tear Garden at the time. Listening to Skinny Puppy back then was part of retracing cEvin Keys first steps, and I fell in love with what I heard.

I lost track of Skinny Puppy’s output until Weapon came out in 2013. Later still I backed-tracked again to listen to the three albums they put out between 2004 and 2011. Of those I think hanDover may be my favorite. I still followed along with Key here and there, and was delighted a few years ago when The Tear Garden put out The Brown Acid Caveat, wonderfully lysergic, if a bit of a bum trip. Yet if it hadn’t been for the darkness and melancholy I don’t know if I would have listened in the first place. When I first heard Skinny Puppy was going on tour I got terribly excited and made sure to get a ticket as soon as I could. The tour was slated at their 40th anniversary and Final Tour, so now was the chance to go if I was going to go. By the time the Friday of the show rolled around my anticipation was peaking. I’d done my homework over the past few weeks and gone back and relistened to some of my old favorite songs and several favorite albums, along with some of the others I’d never listened to as often. When I saw the line to get inside Bogart’s was going all the way down the short side of Short Vine, down Corry St. towards Jefferson, I realized I was going to be standing in the longest line I’d ever been in for a concert at Bogarts. The only others I can remember that were maybe as long were for my first punk show ever, Rancid with The Queers, or later, Fugazi. Being in line for this show was similar to that first concert I went to as a young and aspiring skater punk: I felt a sense of unity being there with a bunch of misfit freaks. I felt at home, and normal for a couple hours. I was also happy to know that: Goths Not Dead. Goth may not be in the same advanced and glorious state of gloom and decay as was when Charles Baudelaire roamed the streets Paris, or when Edgar Allan Poe rued America’s imagination, but those who love the imagery of death are very much alive. Also, I’ve never seen so many Bauhaus and Peter Murphy T-Shirts in one place. Granted, a lot of these goths were aging goths and rusting industrial music rivetheads. A large contingent seemed to be middle-aged like me, in their forties, but others were in their fifties, sixties and a few beyond. I wasn’t sure how many newer fans Skinny Puppy had generated but there were a lot of young people too. These included the children of just-now-having-kids Gen Xers and older Millenials who had brought several 6 to 10 year olds to join in the fray. I guess that shouldn’t have been surprising to me, as I had taken my grandson, then about nine, to see Lustmord when he came to Columbus to do a set at the CoSci planetarium. Either way it was good to see that the intertwined Gothic and Industrial subcultures are not only still alive, but apparently reproducing. The show had sold out and inside the place was packed. It seems obvious that industrial music still resonates. Even as the industrial system that inspired this type of music has long been in decline, our society still grapples with its after effects. Machines have wreaked havoc on human relations, and industrial music still grapples with our relationship troubled relationship to technology. The opening band Lead Into Gold made some pretty mean electronic cuts. I liked all the instrumental aspects of the band, and they had some chest thumping bass. I’m glad I don’t need a pacemaker, because if I did I would have worried it might get jarred loose from the vibrations. This was the side project of Paul Barker, aka Hermes Pan, former bassist for Ministry, and as such I can see why it left me a bit in the middle. Ministry had reliably been a band I always felt stuck in the middle on. I didn’t much care for the vocal side of Lead Into Gold’s performance and they did little to interact with the audience. They weren’t bad, I just would have liked them better sans vocals. During the intermission the palpable pressure continued to build until the lights dimmed, the members of Skinny Puppy came on stage, and the first strains of “VX Gas Attack” slipped out of the speakers. The song uses the sampled word “Bethlehem” among others, and I knew was in some kind of embattled holy land for the duration of the concert. Ogre started off behind a white screen, singing, doing shadow puppet maneuvers, as his growls and inflections pummeled the gathered masses, the drums assaulted and electronics laid everything in a thick bed. By the time the third song “Rodent” came on, Ogre was out from behind the veil, wearing a long dark cloak, face covered in shadows. Then the cloak came down to reveal Ogre as an alien with green lit up eyes that pulsed down on the audience. Another player prowled the stage with him, brandishing a kind of cattle prod or taser. Whatever little sanity was left in the crowd disappeared. The alien wasn’t here to torture us earthlings, but had come and gotten tortured as an alien. The alien hadn’t come to earth to abduct, torture or experiment on any in the crowd, but had come down and was now subject to being prodded, probed, manipulated, and perhaps even vivisected at the hands of humans. I saw this aspect of the performance as a perfect metaphor for our own state of affairs at this time within the larger culture; this time where we are more alienated from each other than we have ever been before, at least in my memory as a tail end Gen Xer. We live in a time of massive projection, of what Carl Jung called “the shadow”. These are the blind spots of our psyches, the places where all the things we refuse to acknowledge got to live. In our society, with all the things we repress and suppress, the contents of the shadow are bound to bubble up as a kind of crude oil used to fuel both sides of the forever culture wars. Since we refuse to look in the mirror at our own shadows, at the alien inside of us, we must find that alien other, prod, tase, torture and beat them down. I had expected to see a montage of horror movie clips projected behind the band, the kind of stuff that might traumatize me for the rest of my life. That wasn’t part of the show, but it didn’t need to be. They did use abstract imagery behind them, but the interaction between ogre and the cattle prodder on stage was more than engaging. Now I love Ogre’s vocals, but the main draw for me as a Skinny Puppy fan has always been the electronic wizardry of cEvin Key. It was fun to watch Key playing, but as I got jostled about in the slew of people, I at first couldn’t see him so well. I was finally able to get into a spot where I could see all the players doing their thing. This leads me to the drummer. I hadn’t expected to see one there. Previous accounts of their live shows noted the use of drum machines. The live drummer was a real plus to the overall experience of the event. He beat the hell out of those drums and the sound was great, matching up expertly to all the songs. Eventually as the music at the show built to the first climax a giant brain was brought out on stage, and the player with taser or cattle prod went straight at it, hitting the brain in rhythm, just like the electrical pulses from the music pulsed my own head. As the concert wound down they took the music all the way back to the beginning with “Dig It,” the last song before the first encore. When they came back on stage, it was just Key and the guitarist Matthew Setzer, engaging in an electronic jam or “Brap.” This could have gone on a lot longer in my opinion. These extended freakout sessions were some of my favorite output of material from their archives. Then Ogre came back out without his costume and ripped into “Gods Gift (Maggot)” before launching into “Assimilate.” A second encore brought them back with another oldie “Smothered Hope” and they ended the whole thing with their more recent song “Candle.” There is something about Skinny Puppy that is tribal. It’s like they were able to draw something out of the terroir of the land they grew up and lived on, and infused that Cascadian vibe into the music. Last year I listened to an interview done by cEvin Key with his fellow Vancouver friends Bill Leeb and Rhys Fulber (of Front Line Assembly, Delerium). They were talking about the scene in the early days, as the Canadian iteration of industrial music developed with the birth of Skinny Puppy. Key talked about being able to walk to anything that was happening, and not needing a car, and how that was an advantage of those early days in the late 70s and early 80s. It got me thinking, as they bantered back and forth about taking drugs, walking around with big poofed up hair, kind of like a gothed out version of glam, of how tribalistic that scene must have been for them. The creativity that was coming to them seemed to come not only from the music they were listening to that was inspiring them (Nocturnal Emissions, Throbbing Gristle, early electronics, lots of punk) but also the energy of the land itself. The kind of industrial music that came out of Vancouver had its own particular flavor. It only could have come from there, as the consciousness of the land spilled into the people making the music. This idea about the terroir of music was later born out by another interview I listened to on Key’s YouTube channel, about the making of the album Too Dark Park -and one of the Vancouver parks the members of the band spent a lot of time hanging out at, and the ancient Native American burial sites within the park. I was grateful to be able to share this tribal experience with the band on stage, and feel the sense of camaraderie with the others in the crowd. All these weeks later I am still going back and forth over it in my head, assimilating the download of their specific style of industrial sound, born in Vancouver and spread around the world.

2 Comments

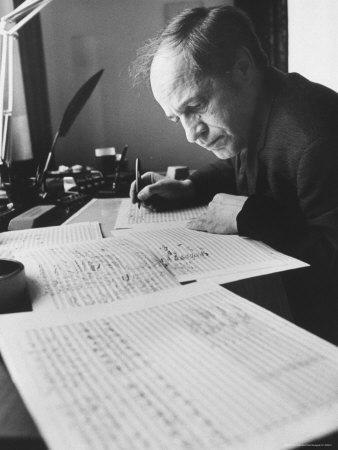

Pierre Boulez was of the opinion that music is like a labyrinth, a network of possibilities, that can be traversed by many different paths. Music need not have a clearly defined beginning, middle and end. Like the music he wrote, the life of Boulez did not follow a single track, but shifted according to the choices available. Not all of life is predetermined, even if the path of fate has already been cast. Choices remain open. Boulez held that music is an exploration of these choices. In an avantgarde composition a piece might be tied together by rhythms, tone rows, and timbre. A life might be tied together by relationships, jobs and careers, works made and things done. The choices Boulez made take him through his own labyrinth of life. As Boulez wrote, “A composition is no longer a consciously directed construction moving from a ‘beginning’ to an ‘end’ and passing from one to another. Frontiers have been deliberately ‘anaesthetized’, listening time is no longer directional but time-bubbles, as it were…A work thought of as a circuit, neither closed nor resolved, needs a corresponding non-homogenous time that can expand or condense”. Boulez was born in Montbrison, France on March 26, of 1925 to an engineer father. As a child he took piano lessons and played chamber music with local amateurs and sang in the school choir. Boulez was gifted at mathematics and his father hoped he would follow him into engineering, following an education at the École Polytechnique, but opera music intervened. He saw Boris Godunov and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and had his world rocked. Then he met the celebrity soprano Ninon Vallin, the two hit it off and she asked him to play for her. She saw his inherent and talent and helped persuade his father to let him apply to the Conservatoire de Lyon. He didn’t make the cut, but this only furthered his resolve to pursue a life path in music. His older sister Jeanne, with whom he remained close the rest of his life, supported his aspirations, and helped him receive private instruction on the piano and lessons in harmony from Lionel de Pachmann. His father remained opposed to these endeavors, but with his sister as his champion he held strong. In October of 1943 he again auditioned for the Conservatoire and was struck down. Yet a door opened when he was admitted to the prepatory harmony class of Georges Dandelot. Following this his further ascension in the world of music was swift. Two of the choices Boulez made that was to have a long-lasting impact on his career was his choice of teacher, Olivier Messiaen, who he approached in June of 1944. Messiaen taught harmony outside the bounds of traditional notions, and embraced the new music of Schoenberg, Webern, Bartok, Debussy and Stravinsky. In February of 1945 Boulez got to attend a private performance of Schoenberg’s Wind Quartet and the event left him breathless, and led him to his second influential teacher. The piece was conducted by René Leibowitz and Boulez organized a group of students to take lessons from him for a time. Leibowitz had studied with Schoenberg and Anton Webern and was a friend of Jean Paul Sartre. His performances of music from the Second Viennese School made him something of a rock star in avant-garde circles of the time. Under the tutelage of Leibowitz, Boulez was able to drink from the font of twelve tone theory and practice. Boulez later told Opera News that this music “was a revelation — a music for our time, a language with unlimited possibilities. No other language was possible. It was the most radical revolution since Monteverdi. Suddenly, all our familiar notions were abolished. Music moved out of the world of Newton and into the world of Einstein.” The work of Leibowitz helped the young composer to make his initial contributions to integral serialism, the total artistic control of all parameters of sound, including duration, pitch, and dynamics according to serial procedures. Messiaen’s ideas about modal rhythms also contributed to his development in this area and his future work. Milton Babbitt had been first in developing has own system of integral serialism, independently of his French counterpart, having published his book on set theory and music in 1946. At this point the two were not aware of each others work. Boulez’s first works to use integral serialism are both from 1947: Three Compositions for Piano and Compositions for Four Instruments. While studying under Messiaen Boulez was introduced to non-western world music. He found it very inspiring and spent a period of time hanging out in the museums where he studied Japanese and Balinese musical traditions, and African drumming. Boulez later commented that, "I almost chose the career of an ethnomusicologist because I was so fascinated by that music. It gives a different feeling of time." In 1946 the first public performances of Boulez’s compositions were given by pianist Yvette Grimaud. He kept himself busy living the art life, tutoring the son of his landlord in math to help make ends meet. He made further money playing the ondes Martentot, an early French electronic instrument designed by Maurice Martentot who had been inspired by the accidental sound of overlapping oscillators he had heard while working with military radios. Martentot wanted his instrument to mimic a cello and Messiaen had used it in his famous symphony Turangalîla-Symphonie, written between 1946 and 1948. Boulez got a chance to improvise on the ondes Martentot as an accompanist to radio dramas. He also would organize the musicians in the orchestra pit at the Folies Bergère cabaret music hall. His experience as a conductor was furthered when actor Jean-Louis Barrault asked him to play the ondes for the production of Hamlet he was making with his wife, Madeline Reanud for their new company at the Théâtre Marigny. A strong working relationship was formed and he became the music director for their Compagnie Renaud-Barrault. A lot of the music he had to play for their productions was not to his taste, but it put some francs in his wallet and gave him the opportunity to compose in the evening. He got to write some of his own incidental music for the productions, tour South America and North America several times each, in addition to dates with the company around Europe. These experiences stood him well in stead when he embarked on the path of conductor as part of his musical life. In 1949 Boulez met John Cage when he came to Paris and helped arrange a private concert of the Americans Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano. Afterwards the two began an intense correspondence that lasted for six-years. In 1951 Pierre Schaeffer hoste the first musique concrète workshop. Boulez, Jean Barraqué, Yvette Grimaud, André Hodeir and Monique Rollin all attended. Olivier Messiaen was assisted by Pierre Henry in creating a rhythmical work Timbres-durè es that was mad from a collection percussive sounds and short snippets. At the end of 1951, while on tour with the Renaud-Barrault company he visited New York for the first time, staying in Cage’s apartment. He was introduced to Igor Stravinksy and Edgard Vaèse. Cage was becoming more and more committed to chance operations in his work, and this was something Boulez could never get behind. Instead of adopting a “compose and let compose” attitude, Boulez withdrew from Cage, and later broke off their friendship completely. In 1952 Boulez met Stockhausen who had come to study with Messiaen, and the pair hit it off, even though neither spoke the others language. Their friendship continued as both worked on pieces of musique concrète at the GRM, with Boulez’s contribution being his Deux Études. In turn, Boulez came to Germany in July of that year for the summer courses at Darmstadt. Here he met Luciano Berio, Luigi Nono, and Henri Pousseur among others, and found himself moving into a role as an acerbic ambassador for the avantgarde. Sound, Word, Synthesis As Boulez got his bearings as a young composer, the connections between music and poetry came to capture his attention, as it had Schoenberg. Poetry became integral to Boulez’s orientation towards music, and his teacher Messiaen would say that the work of his student was best understood as that of a poet. Sprechgesang, or speech song, a kind of vocal technique half between speaking and singing, was first used in formal music by Engelbert Humperdink in his 1897 melodrama Königskinder. In some ways sprechgesang is a German synonym for the already established practice of the recitative in operas as found in Wagner’s compositions. Arnold Schoenberg used the related term Sprechstimme as a technique in his song cycle Pierrot lunaire (1912) where he employed a special notation to indicate the parts that should be sung-spoke. Schoenberg’s disciple Alban Berg used the technique in his opera Wozzeck (1924). Schoenberg employed it again in his Moses and Aron opera (1932). In Boulez’s explorations of the relationship between poetry and music he questioned "whether it is actually possible to speak according to a notation devised for singing. This was the real problem at the root of all the controversies. Schoenberg's own remarks on the subject are not in fact clear." Pierre Boulez wrote three settings of René Char's poetry, Le Soleil des eaux, Le Visage nuptial, and Le Marteau sans maître. Char had been involved with Surrealist movement, was active in the French Resistance, and mixed freely with other Parisian artists and intellectuals. Le Visage Nuptial (The Nuptial Face) from 1946 was an early attempt at reuniting poetry and music across the gap they had taken so long ago. He took five of Chars erotic texts and wrote the piece for two voices, two ondes Martenot, piano and percussion. In the score there are instructions for “Modifications de l’intonation vocale.” His next attempt in this vein was Le Marteau sans maître (The Hammer without a Master, 1953-57) and it remains one of Boulez’s most regarded works, a personal artistic breakthrough. He brought his studies of Asian and African music to bear on the serialist vortex that had sucked him in, and he spat out one of the stars of his own universe. The work is made up of four interwoven cycles with vocals, each based on a setting of three poems by Char taken from his collection of the same name, and five of purely instrumental music. The wordless sections act as commentaries to the parts employing Sprechstimme. First written in 1953 and 1954, Boulez revised the order of the movements in 1955, while infusing it newly composed parts. This version was premiered that year at the Festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music in Baden-Baden. Boulez had a hard time letting his compositions, once finished, just be, and tinkered with it some more, creating another version in 1957. Le Marteau sans maître is often compared with Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire. By using Sprechstimme as one of the components of the piece, Boulez is able to emulate his idol Schoenberg, while contrasting his own music from that of the originator of the twelve tone system. As with much music of the era written by his friends Cage and Stockhausen, the work is challenging to the players, and here most of the challenges are directed at the vocalist. Humming, glissandi and jumps over wide ranges of notes are common in this piece. The work takes Char’s idea of a “verbal archipelago” where the images conjured by the words are like islands that float in an ocean of relation, but with spaces between them. The islands share similarities and are connected to one another, but each is also distinct and of itself. Boulez took this concept and created his work where the poetic sections act as islands within the musical ocean. A few years later, he worked with material written by the symbolist and hermetic poet Stéphane Mallarme, when he wrote Pli selon pli in (1962). Mallarme’s work A Throw of the Dice is of particular influence. In that poem the words are placed in various configurations across the page, with changes of size, and instances of italics or all capital letters. Boulez took these and made them correspond to changes to the pitch and volume of the poetic text. The title comes from a different work by Mallarme, and is translated as “fold according to fold.” In his poem Remémoration d'amis belges, he describes how a mist gradually covers the city of Bruges until it disappears. Subtitled A Portrait of Mallarme Boulez uses five of his poems in chronological order, starting with "Don du poème" from 1865 for the first movement finishing with "Tombeau" from 1897 for the last. Some consider the last word of the piece, mort, death, to be the only intelligible word in the work. The voice is used more for its timbral qualities, and to weave in as part of the course of the music, than as something to be focused on alone. Later still Boulez took e.e. cummings poems and used them as inspiration for his work Cummings Ist der Dichter in 1970. Boulez worked hard to relate poetry and music together in his work. It is no surprise, then, that the institute he founded would go far in giving machines the ability to sing, and foster the work of other artists who were interested in the relationships between speech and song. Ambassador of the Avantgarde

At the end of the 1950s Boulez had left Paris for Baden-Baden where he had scored a gig as composer in residence with the South-West German Radio Orchestra. Part of his work consisted of conducting smaller concerts. He also had access to an electronic studio where he set to work on a new piece, Poesie Pour Pouvoir, for tape and three orchestras. Baden-Baden would become his home, and he eventually bought a villa there, a place of refuge to return to after his various engagements that took him around the world and on extended stays in London and New York. His experience conducting for the Théâtre Marigny, had sharpened his skills in this area, making it all possible. Boulez had gained some experience as a conductor in his early days as a pit boss at the Folies Bergère. He gained further experience when he conducted the Venezuela Symphony Orchestra when he was on tour with his friend Jean-Louis Barrault. In 1959 he was able to get further out of the mold of conducting incidental music for theater and get down to the business he was about: the promotion of avantgarde music. The break came when he replaced the conductor Hans Rosbaud who was sick, and a replacement was needed in short notice for a program of contemprary music at the Aix-en-Provence and Donaueschingen Festivals. Four years later he had the opportunity to conduct Orchestre National de France for their fiftieth anniversary performance of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, where the piece had been first been premiered to the shock of the audience. Conducting suited Boulez as an activity for his energies and he went on to lead performances of Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck. This was followed by him conducting Wagner’s Parsifal and Tristan and Isolde. In the 1970s Boulez had a triple coup in his career. The first part of his tripartite attack for avantgarde domination involved his becoming conductor and musical director the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Then second part came after Leonard Bernstein’s tenure as conductor of the New York Philharmonic was over, and Boulez was offered the opportunity to replace him. He felt that through innovative programming, he would be able to remold the minds of music goers in both London and New York. Boulez was also fond of getting people out of stuffy concert halls to experience classical and contemporary music in unusual places. In London he gave a concert at the Roundhouse which was a former railway turntable shed, and in Greenwich Village he gave more informal performances during a series called “Prospective Encounters.” When getting out of the hall wasn’t possible he did what he could to transform the experience inside the established venue. At Avery Fisher Hall in New York he started a series of “Rug Concerts” where the seats were removed and the audience was allowed to sprawl out on the floor. Boulez wanted "to create a feeling that we are all, audience, players and myself, taking part in an act of exploration". The third prong came when he was asked back by the President of France to come back to his home country and set up a musical research center. Read the rest of the Radio Phonics Laboratory: Telecommunications, Speech Synthesis and the Birth of Electronic. Selected Re/sources: Benjamin, George. “George Benjamin on Pierre Boulez: 'He was simply a poet.'” < https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/mar/20/george-benjamin-in-praise-of-pierre-boulez-at-90> Boulez, Pierre. Orientations: Collected Writings. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1986. Glock, William. Notes in Advance: An Autobiography in Muisc. Oxford, UK.: Oxford University Press. 1991. Greer, John Michael. “The Reign of Quantity.” < https://www.ecosophia.net/the-reign-of-quantity/> Griffiths, Paul. “Pierre Boulez, Composer and Conductor Who Pushed Modernism’s Boundaries, Dies at 90.” < https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/07/arts/music/pierre-boulez-french-composer-dies-90.html> Jameux, Dominique. Pierre Boulez. London, UK.: Faber & Faber, 1991. Peyser, Joan. To Boulez and Beyond: Music in Europe Since the Rite of Spring. Lanham, MD.: Scarecrow Press, 2008 Ross, Alex. “The Godfather.” <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2000/04/10/the-godfather> Sitsky, Larry, ed. Music of the 20th Century Avant-Garde: A Biocritical Sourcebook. Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 2002. |

Justin Patrick MooreAuthor of The Radio Phonics Laboratory: Telecommunications, Speech Synthesis, and the Birth of Electronic Music. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed