|

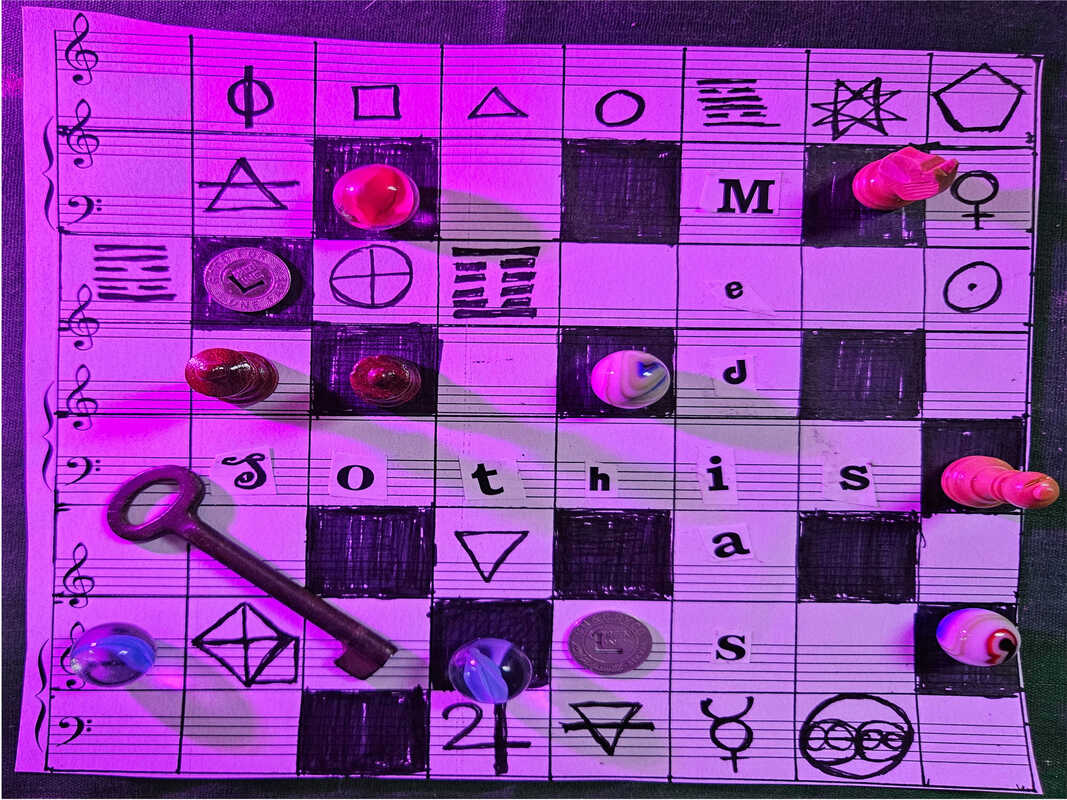

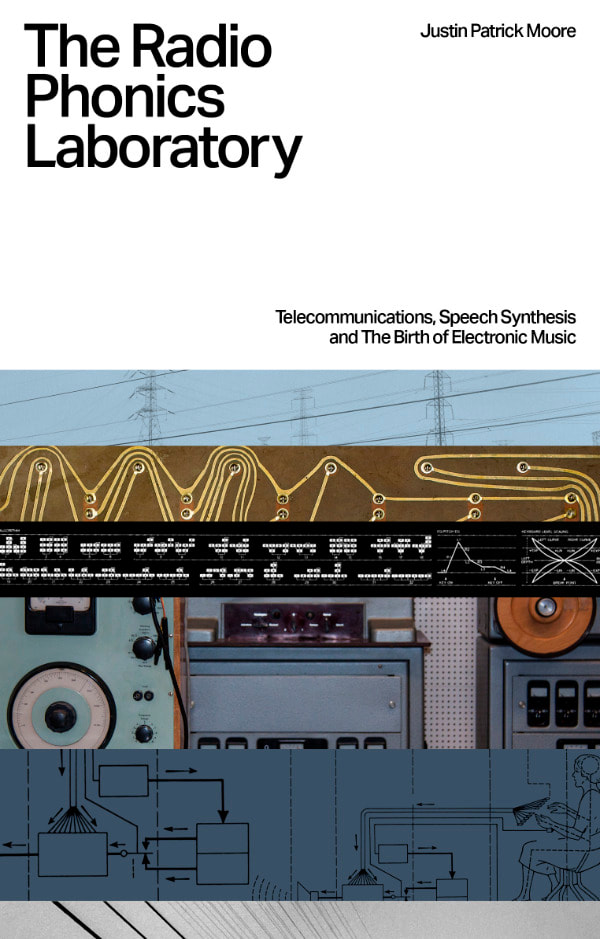

Things have been quiet around here, but I have been very busy inside my secret workshop since this past fall when my book, The Radio Phonics Laboratory, was accepted for publication by the wonderful atelier of electronica, Velocity Press. Now my book is finally ready to begin its escape from the lab and is available for pre-order. Some of you may have read the original articles that make up this book in earlier forms here on Sothis Medias, or in the Q-Fiver, the newsletter of the Oh-Ky-In Amateur Radio Society where they had their first genesis, but this book has the additional benefit of several rewrites, the hand of a skilled editor, and much additional material not included in my original articles. It also has the bonus that if you pre-order by March 14 you will get your name printed in the book and receive it first in May for those of us in North America. The Radio Phonics Laboratory is due for release on June 14 but because the publisher is in England, it won't be readily available in the US until late summer or early fall. They have to get the copies in from the printers and ship them to their distributor in California. Pre-ordering is the best option for supporting my work, the efforts of Velocity Press, and getting a copy in your hands ahead of time for summer reading. The price is £11.99 for the paperback (about $15.16 US) + shipping. The shipping to the US is a bit more expensive than domestic shipping prices, but you'll get your name printed in the book as a supporter if you order before March 14 and you'll have my gratitude. This book is the culmination of many seeds, some planted long ago when I first started checking out weird music from the library as a teenager and stumbled across the CD compilation Imaginary Landscapes: New Electronic Music and tuned in to radio shows like Art Damage. This is the culmination of many many hours of research, listening, reading and writing over for a number of years. Full details about the book are below. Thanks to all of you for supporting my writing and radio activity and other creative efforts over the years. I would be grateful for any help you can give in spreading the word about the Radio Phonics Laboratory to any of your friends and family who share the love of electronic music, the avant-garde and the history of our telecommunications systems. https://velocitypress.uk/product/radio-phonics-laboratory-book/ The Radio Phonics Laboratory explores the intersection of technology and creativity that shaped the sonic landscape of the 20th century. This fascinating story unravels the intricate threads of telecommunications, from the invention of the telephone to the advent of global communication networks.

At the heart of the narrative is the evolution of speech synthesis, a groundbreaking innovation that not only revolutionised telecommunications but also birthed a new era in electronic music. Tracing the origins of synthetic speech and its applications in various fields, the book unveils the pivotal role it played in shaping the artistic vision of musicians and sound pioneers. The Radio Phonics Laboratory by Justin Patrick Moore is the story of how electronic music came to be, told through the lens of the telecommunications scientists and composers who helped give birth to the bleeps and blips that have captured the imagination of musicians and dedicated listeners around the world. Featuring the likes of Leon Theremin, Hedy Lamarr, Max Matthews, Hal 9000, Robert Moog, Wendy Carlos, Claude Shannon, Halim El-Dabh, Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry, Francois Bayle, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Vladimir Ussachevsky, Milton Babbitt, Daphne Oram, Delia Derbyshire, Edgar Varese & Laurie Spiegel. Quotes “From telegraphy to the airwaves, by way of Hedy Lamarr and Doctor Who, listening to Hal 9000 sing to us whilst a Clockwork Orange unravels the past and present, Moore spirits us on an expansive trip across the twentieth century of sonic discovery. The joys of electrical discovery are unravelled page by page.” Robin Rimbaud aka Scanner “Embark on an odyssey through the harmonious realms of Justin Patrick Moore’s Radio Phonics Laboratory echoing the resonances of innovation and discovery. Witness the mesmerising fusion of telecommunications and musical evolution as it weaves a sonic tapestry, a testament to the boundless creativity within the electronic realm. A compelling pilgrimage for those attuned to the avant-garde rhythms of technological alchemy.” Nigel Ayers “In this captivating exploration of electronic music, Justin Patrick Moore unveils its evolution as guided by telecommunication technology, spotlighting the enigmatic laboratories of early experimenters who shaped the sound of 20th century music. A must-read for electronic musicians & sound artists alike—this book will undoubtedly find a prominent place on their bookshelves.” Kim Cascone

0 Comments

If the Muses inspire the pens of poets, then it was the spring sacred to the Muses that Herman Hesse drank from when he dreamed up the concepts in his inspired masterpiece, The Glass Bead Game. Castalia is the main setting for the book, a fictional province somewhere in central Europe, some centuries in the future. The province had been set apart as a place for the development of the mind. Individuals who are deemed to be worthy of attending the boarding schools of Castalia are sent their and educated by an order of intellectuals and mystics. The life in the order is much like that in a monastery, yet in Castalia the devotees of the order cultivate and play something known as the Glass Bead Game. Throughout the book the exact nature of the game is never spelled out in full, and the reader is expected to imagine what the nature of the game is by inference. To play the game well a person needs to have an encyclopedic grasp of mathematics, music, the arts, science, religion, and cultural history. At its most basic it could be described as a game where the player makes connections between different fields of study that may at first seem unrelated. A well-played game becomes an act of creative synthesis showcasing the beauty of the connections formed, of the different subjects threaded and woven together. Playing the game is an active form of contemplation for the Castalian, as is watching a game being played by a master player. The meaning of the game, and any connections made during its play, become further objects for exploration in contemplative meditation as taught by the order. Music has a special place in Castalia. In the hierarchy of what they hold dear it is one rung below the game itself. Young acolytes are trained in music from an early age, and music is often incorporated directly into the games. Hesse gave a number of precedents that he conceived of as influencing the eventual development of the game. These included the Music of the Spheres, beloved of the Pythagoreans, systems and ideas of a Universal Language, and scholastic philosophy among many others. But why give the province the name Castalia in the first place? To answer this question we turn to Greek mythology. Castalia was a naiad, a kind of nymph or nature spirit, that preside over springs, fountains and streams, often living in them. The difference between the spring itself and the naiad can be blurry for those who try to separate the spirit from the matter. Castalia was the daughter of the River God Achelous. She either threw herself into the spring, or was transformed into a spring, in the course of trying to evade the creeping advances of Apollo, God of music, knowledge and oracles. The spring took on her name and became a sacred source of inspiration to Apollo, her would be suitor, and the Muses. The location of the spring, or fountain as it is sometimes also described, happened to be on the sloped base of Mount Parnassus. This mountain range in Greece was long held sacred, on the one hand to Dionysius and those who were initiated in his mysteries, and on the other to Apollo and the Muses. Delphi itself was situated on the southern side of the mountain. The ancient Latin poet Lactantius Placidus said Castalia had transformed herself into a fountain right at Delphi. Apollo then consecrated this source of water to the Muses. Those who drank her waters, or even those who sat next to the spring and listened to the liquid trickle, would become inspired by the genius or daimon of poetry. These same waters were said to be used to cleanse the temples at Delphi. By calling his province Castalia, Hesse invokes the power of the Muses and of Apollo. The Muses are the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, memory, their mother who presides over them. These are the Greek deities of intellectual and artistic pursuit, of poetry, literature, music, astronomy, philosophy, dance, and history. Apollo, was among other things, a god of prophecy and it was he was the god of the oracle of Delphi, the most important of all the oracles in ancient Greece. Though Delphi was his chief oracular shrine, there were others sacred to the god. Branchidae and Claros, both in Iona, were also places where people sought his wisdom. It seems that Hesse chose the name Castalia because of its connection to Apollo and because of the oracular nature of the Glass Bead Game itself. Being a game of rich symbolic connections, and a game that sometimes involves the play of chance, and the intuition and knowledge of the player gives it an oracular nature in way that is similar to methods of divination that may have started in some instances as games, such as the tarot. Other diviniation systems such as the I Ching may not have started as games, but later take on elements from games, such as coin tossing and dice throwing. One way to think of divination is as a consultation with spirits, gods, or the intelligent life force active in the universe. In ancient Greek religion people took consultation with the Gods as a given. They believed, much as the more familiar Christians of the past two thousand years have believed, that establishing a line of communication with their deity would allow them to receive divine wisdom. They prayed for success in life, strength to overcome difficulties, and hoped to court the personal favor of the Gods and Goddesses with various offerings and rituals. Apollo was a favored choice among the Greeks when they needed to know the future. Being a god of prophecy made him a natural fit for those who wanted to take a peek ahead and try to see what was around the corner for them in life. His prophetic side is only one aspect of this deity. Apollo is a god of music, medicine, and archery, as well shepherds and their flocks. He is seen as giving order and purpose to civilization, assisting in its development, as well as with endowing codes and laws. Philosophy is pleasing to Apollo. Hesse would have been very familiar with the idea of the dichotomy between Dionysian modes of culture and Apollonian, a theme very much alive from the time of the German art historian and Hellenist Johann Joachim Winckelmann on up to the work of the German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin. The literary theme was taken the furthest and made most well-known by philosopher Friedrich Nietszche in his work The Birth of Tragedy. To gloss a complex line of thinking it can first be noted that Dionysus and Apollo are both sons of Zeus, though with different mothers. Dionysus, ruled over wine, dancing, pleasure seeking, and importantly, all things chaotic and irrational. He is associated with primal instincts and passion, the primacy of emotion, and was the son of Semele. Though not a god of the moon per se, Dionysus can be thought of as relating to the lunar current in humanity and those things associated with it such as dreams and visionary states. Apollo, by contrast, is a solar god, whose orbit encompasses the realms of art, music, logic, order and reason, and is the son of Leto. These brothers, often at odds with each other in their personality, and in things over which they each have been given control, were not seen as opposites by the Greeks. Instead they were thought to be deeply enmeshed with one another. Still, that didn’t stop later thinkers from seeing within their interplay something of the yin and yang. The mode of life in Hesse’s Castalia is the epitome of order and reason. There is a deep mysticism and embrace of the spiritual by the Castalians through their practices of study, meditation, and contemplation. Yet their route to the heights of illumination is taken as a slow gradual step-by-step program or process of spiritual unfoldment. The Dionysian mode by contrast is perhaps best represented by what Arthur Rimbaud called the “systematic derangement of the senses” through means of intoxication, visionary drugs, and losing oneself in the ecstasy of dance and passion. Illumination can come that way, but for dabblers, it is often at steep costs. As such as Apollo is the appropriate god to see over the unfoldment of Hesse’s future province. How Apollo came to be a god regarded as prophetic is not known, though his civilizing aspects goes way back into olden times with him being a god of the shepherd where his skills in medicine, archery and music would all be appreciated. The string that makes a bow for an arrow can also be used to make a lyre. There were other beings and energies associated with Delphi aside from Castalia, and even more famous, namely, Python. This dragon or serpent was said to live in the center of the earth, and before Apollo came to kill him, he presided over the oracle which existed at that spot as a cult for Gaia. The Greeks believed that Zeus had made this spot the navel of the world, in other words the axis mundi, or to say it another way, the center of the world. They used a stone called the omphalos to mark the exact spot. Python guarded this stone and when Apollo slayed the dragon he set up shop in his place. Every eight years there was a ritual re-enactment of his Apollo’s earliest adventure, the killing of the Python held at the shrine. In the Delphic Septeria ritual, a boy who impersonated the god was led to a place called the Palace of the Python. This was a hut near the temple. They set the hut on fire and the boy was banished from the realm. The ritualists went to the Vale of Tempe to be purified. The Vale of Tempe was a place known in legend. Its deep gorge had been made when Poseidon cut through the rocks with his trident. The place was a favorite hangout spot for Apollo and the Muses, and was later home for a time to Aristaeus, his son with Cyrene, a Thessalian princess who later became the queen and ruler of her namesake city Cyrene, in Libya, North Africa. Aristaeus offended the nymphs when he chased after Eurydice, causing her to be bitten by a serpent and die. Seeking revenge, the nymphs destroyed his beehives. Going to his mother, she suggests he seek the wisdom of Proteus, a god of the sea. Proteus explains to him the cause of his misfortune, and his mother recommends he sacrifice his cattle to the nymphs. When he returns nine days later after the slaughter, he finds the carcasses of the cattle to be swarming with bees. There is a correspondence here with the bees who made honey in the skull of the lion after the biblical Samson slayed a lion, and when he returned, noticed a swarm of bees and some honey it’s carcass. The Pineios river flowed through the Vale of Tempe on its right bank was a temple of Apollo. It was hear where the bay laurels used to crown the victors in the Pythian Games were gathered. After purification in Tempe the adherents to the ritual came back by a path known as the Pythian Way. This whole enactment was a way of commemorating the dragon slayer.

Visitors would come to the oracle and ask a question of the Pythia, the high priestess, who would then deliver cryptic lines and verses of advice. The Pythia sat on bronze tripod over a crack in the earth where Python had gone inside to die. The fumes from his rotting corpse emanated up from the crack to help the Pythia enter into her oracular trance. The Pythia was also trained in the teachings of the Mystery Schools of the time and she learned the spiritual and magical techniques needed to communicate the messages of Apollo to the people who came seeking his wisdom. At the beginning of each day, before sitting on her special throne she purified herself in the sacred waters of the Castalian spring. Though the site was remote, it was situated on an important trade route between north Greece and Corinth, allowing people from all across the land to come and seek the wisdom of Apollo. There is another similarity between Delphi and the Castalia of Hesse’s novel. Unlike other sacred sites in Greece, it was not attached to a city-state. Instead, it was protected by a council known as the Amphictyonic League. These leagues were charged with the maintenance and care of the temples. The province of Castalia in the book is kept separate for the most part from the economic life of the surrounding countries, so they will be free to pursue their intellectual pursuits. The Amphictionies helped maintain the Oracle of Delphi as a neutral space. Castalia also seems to have another parallel to the neutrality of Switzerland where Hesse emigrated had emigrated from Germany. The Amphictionies were also charged with holding the Pythian Games, just the Order who ran Castalia held a major festival for the play of the Glass Bead Game. The Pythian Games were a competition in music. This is another parallel. The Pythian Games weren’t as popular as the Olympian, with their focus on athleticism. There focus had been on the creation of a hymn to Apollo. These would be sung with accompaniment on the cithara, a seven stringed version of the lyre that was seen as more professional and less country bumpkin. At first the Pythian Games were held every eighth year, just as the Delph Septeria was, but they were later reorganized by the Amphictionic Council, and held on every third year of the Olympiad. The competition involved singing, instrumental music, drama, and the recitations of poetry and prose. Races on foot and horse were later added after the Olympian Games, which honored Zeus. The prize for winning was a crown of bay leaves brought from the valley of Tempe. Getting a consultation at the oracle wasn’t just something you could go up and do anytime you needed a word of advice. There was an elaborate process around the whole shebang. Access was limited. People could only consult the Oracle once a month for nine months of the year. Apollo took a vacation the rest of the year. It was believed he left for the winter to go to warmer climates. Given the limited time span when he was available, it might be thought, that like in today’s world, only the wealthy would be able to utilize such a precious resource. Yet anyone could visit the oracle of Delph, though there was another hierarchy based on where people came from came into play. Even so, all mortals were just mortals to Apollo. Sometimes all it takes to get the mental wheels spinning along new grooves is listening to a good mix. This was most definitely the case when I tuned into a three hour special of the radio show Do or DIY from Vicki Bennett aka People Like Us on WFMU this past Valentines Day. Her mixture of “pop and avant-garde side by side, sometimes on top of one another” has been a mainstay of my radio listening habits since somewhere between 2007 and 2009 by my best guestimation, though her archives for that particular aspect of her creative work go all the way back to 2003. There are hours and hours of great music there. Her shows always make me laugh and smile, and its refreshing to have humorous music on the air. The episode in question was, “This Is Bardcore This Is Barcode This is the Pooless Flute.” The Pooless Flute bit is an in joke that goes back to what she called “pooey flute” –all the shitty cover songs done terribly by people on YouTube on purpose, though technically, I suppose some of it is recorder music. But who is keeping track? This episode was unfortunately pooless, but it did have a few recurring motifs over the course of its very quick three hours. The first was from the bardcore microgenre. A microgenre might as well be called a meme, as Bennett herself put it that way. Often these microgenres function just as much as meme, with artists taking on a certain aesthetic with the use of graphics, phrasing, and other elements as new niches are carved out in what remains of the Internet’s digital playground. The bardcore songs tend to be renditions of popular music done in an electronic quasi-medieval style. Sometimes the genre of bardcore is also called tavernwave, showing its kinship to other microgenres such as vaporwave and mallsoft. It shares the electronic aspect, as most bardcore is made using readily available computer software, as far as I can tell, though I could be wrong in this. Popular artists include Algal the Bard, who originated the style with their cover of a System of A Down’s track “Toxicity.” Hildegard von Blingin’ has been prolific with covers of “Creep” by Radiohead, “Jolene” by Dolly Parton and Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance.” She distinguishes herself by singing over the medieval version, and by slightly altering the lyrics to resemble older forms of English. Beedle the Bard is another prolific bardcore artist. His cover of the Wu Tang classic “C.R.E.A.M.” is representative of the genre, and he has made quite a few covers of rap songs. Rap might even be the majority of what he has covered in his bardcore transformations. Another theme she returned to over the course of the show was various mashups, collages or remixes of the song “Bitter Sweet Symphony” by The Verve. That song came from their album Urban Hymns which has been one of the bestselling albums in UK history. Of the many tracks I loved in this mix was a rap by Ren Gill over the music of Bitter Sweet Symphony. Lyrically it was a cutting and heartfelt commentary on life in London and Britain from the view on the street. And though it was all about London, a city where I’ve never set foot, but traveled to in books, movies, TV shows, and the via the wireless magic of radio, the socioeconomic aspects of the words, juxtaposing not left and right, but top and bottom, resonated with me here in the Midwest. As I listened I felt a strong bond of kinship with my friends across the pond. As my mate One “Deck” Pete says, “Radio connects us all”. After the show was over I went down a bit of a Ren rabbit hole, because I couldn’t get that rap out of my head. It turns out Ren Gill is an amazing guitar player and singular rapper with a gift for narrative. In essence, he could be considered a bardcore rapper. Not because his music makes use of quasi-medieval sounds, but because of his talent and skills of verbal execution put him in league with the lyrical masters of poetic narrative. The dude is a bard. His music is bardcore down to the bone. Plus, he is from Wales. You know, the place that gave us the famous bard Taliesin. Not that Wales has a monopoly on bards. Singing and storytelling are worldwide traditions (consider the griots of West Africa for one of many examples), but Wales was home to the Eisteddfod, the competitive meeting held between bards and minstrels first mentioned in the written record back in the day of the twelfth century. A bloke by the name of Lord Rhys first held the Eisteddfod in 1176 as a competition in poetry and music at Cardigan Castle. When the Wales was conquered by the Edwardians during their conquest in the 13th century, they closed down the existing bardic schools as part of the Anglicization of the countries nobles. Later the Eisteddfod was resuscitated by the Gwyneddigon Society, a group dedicated to Welsh culture, in the 18th century. Later the Eisteddfod was picked up as perfect vehicle for the Gorsedd Cymru, which was steeped in an eclectic alchemical mixture of Druidism, Philosophy, Mysticism and Christianity. The Gorsedd Cymru was itself a revival. A Welshman by the name of Prydain ab Aedd Mawr, who was said to have lived one thousand years before the Christian era, had started the Gorsedd as a means to transmit the work of poets and musicians from generation to generation. In 1792 the Gorsedd was rekindled as Gorsedd Beirdd Ynys Prydain the lovable Rapscallion best known as Iolo Morganwg, given name, Edward Williams. He based the Gorsedd Cymru on his imaginative ideas of Celtic Druidry. The Gorsedd made its first appearance at the Eisteddfod at the Ivy Bush Inn in Carmarthen in 1819, and its close association with the festival has continued since then. I’m not sure at all if Ren has ever been to an Eisteddfod, or what his take might be on things such as Druidry and Celtic infused mysticism. What I do know is that he was born Ren Gill in Bangor, Gwynedd, Wales, on March 29th 1990 and was raised in Dwyran, on the isle of Anglesey (Ynys Môn in Welsh). Anglesey was the last refuge of the Druids before they got stamped out in the ancient times. The isle has long been esteemed as a place of mystical power. Ren had musical aspirations from an early age and after he got a guitar he taught himself how to play it by slowing down the songs of Jimi Hendrix to copy and learn how to play them. Starting with wanting to copy the music of a master is always a good sign! Ren also made beats using the popular computer software Reason and hawked these CDs at the music festivals he wen to with his parents. Ren went to study music at Bath Spa University and while he was there he formed the indie hop-hop group Trick The Fox. From there, in 2009, he caught the eyes of the music industry and signed a record contract with Sony in 2010. He started working on an album but became too sick to complete it and moved back home to Wales. He was bedridden for most of the day due to the severity of his sickness. Thus began a run around between himself and the health system. Symptoms suggested autoimmune illness combined with a mental health crisis, but he was misdiagnosed. He did not in fact have bipolar disorder, he was not in fact psychotic. It took him awhile to get a correct diagnosis of Lyme disease in Belgium in 2016, but by then he had suffered from the treatments received for the wrong disease. In that time, despite his ordeal, he never lost the dream of making it as a musician, and he started working on music as best he could in his bedroom. The same year he got his diagnosis he released his debut solo album Freckled Angels, self released without any help from Sony. This had a bunch of material first used in Trick The Fox. Between 2016 and the time of this writing he has continued to release music. His viral hit “Hi Ren,” came out at the end of 2022 and is one example of why I consider his style bardic. It’s the guitar. It’s the narrative. It is the two points of view, that seemed to have come from him effortless, but are actually the product of his years of effort putting the time in honing his art. Listening to Ren got me thinking again on the topic of epic rap. John Michael Greer has written about how he thinks rap is the seed of a future form of epic poetry. He writes: “I’m not personally fond of rap, as it happens, but I can recognize a vibrant cultural upsurge when I see one. It’s a little dizzying to have a seat on the sidelines while a new tradition of bardic poetry is being born—for that’s what we’re talking about, of course. More than five thousand years ago, performers with a single string instrument for backup created rap numbers celebrating the events of their time; one of those, passed down from performer to performer, eventually got copied down on clay tablets by industrious scribes and titled Shutur Eli Sharri. We know it today as the Epic of Gilgamesh. The same process in other ages, with slightly different backup instruments pounding away to give emphasis to chanted words, gave us the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Song of Roland, Beowulf, and the beat goes on.” Even if we are not at the point where rap is the means for transmitting a cultures epic tales, we are at the point where it is continuing to develop its potential for narrative storytelling. Ted Gioia has pointed out that there is currently a return to narrative in pop music. He writes that, “narrative song is especially well suited to the four-chord patterns that underpin so many current day pop hits. Those repeating harmonic cushions don’t offer much in the way of musical sophistication, but do create ideal vamps for supporting a story—not much different from the gusle drones used by Eastern European bards to underpin their epic tales.” He goes on to say that the reemergence of narrative centered music, after a time when popular songs were mostly lyrical or dance, implicates “a glimpse into an emerging movement in society at large.” When we talk about narrative songs, what we are mostly talking about is the ballad. Ren is another example of this trend. For my part I think a lot of it has to do with the way people crave story. We never got away from story. As postmodernism erupted in the 1960s and 70s, with its fractured and fragmented outlooks, we still had at least elements of narrative and vague outlines of action, even in the most esoteric tomes where it was often hard to pin down a point-by-point plot. Of course the ballad never really disappeared to begin with. It was carried forth by such singers as Shirley Collins and others in the British Folk Revival. The ballad was documented by the likes of Alan Lomax and other song collectors in America. Recordings were transmitted from these collections, and on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. All this traditional songs went on to inform the Folk Revival happening in the United States and influenced Bob Dylan and company, and was championed by beatnik bards such as Allen Ginsberg, who had given us our own homegrown American Romanticism. Dylan studied these old songs like he was cramming for a PhD thesis. He learned to crib, copy and mimic these for his own great artistic purposes. The ballad also had a place in popular country music, which could be considered folk adjacent. The ballad lived on in the heavy metal music of the glam and hair variety in the eighties, where it became a sacharine staple with its sweet guitar solos. In rap, the murder ballad made a reappearance if in altered and different form. Ren’s trilogy of songs The Tale of Jenny and Screech, make for an impressive case that rap really may be on its way to becoming the next form of epic poetry. These long form narrative efforts tell a conclusive story. Broken down into “Jenny’s Story,” “Screech’s Tale,” and “Violet’s Tale.” It’s the kind of thing that you might once have read in a penny dreadful and concerns many of the predicaments facing people today. Domestic abuse, mental illness, drug addiction. The timeless topics of love, incest and murder are also covered. It’s dark material. But so it ever was. The human species is drawn to the form of tragedy so that we may have a chance for catharsis. I’m hopeful that the next time I’m dragged to a renfest by my family, that that there will be more bardcore music being played in the background, quasi medieval versions of contemporary rap songs. With any luck there will be bards, inspired by the example of Ren, wondering around with their guitars, busking and delivering epic narrative raps. If not at a renfest in the coming years, than at some fair or festival held on the fairgrounds in the deindustrial dark age to come. Green Day's album "Dookie" has turned 30. It now gets the deluxe box set reissue treatment. That is kind of weird to me. Perhaps, after thirty years, it is time to put this album in a dog poop bag, and put it into the trash.

Am I being too harsh? Maybe, I finally am. When I first saw this box set it, celebrating its 30th anniversary, it made me feel old. I know that's relative. Suddenly I was back in the eighth grade when this came out, when I was first exposed to the Green Day version of punk rock, fourteen years old, hitting the streets with a skateboard. Sure, Green Day, was more pop than punk, but there were many great pop punk bands that I liked much better. It was the same time in my life when I was getting turned on to the better punk rock music of The Descendants, Minor Threat, Black Flag, Circle Jerks, The Ramones, and later the anarcho-punk that came out England such as Crass, Conflict, Chumbawamba, Flux of Pink Indians and the like. Crass, earyl Chumbawamba and Rudimentary Peni became favorites for me. I really liked that noisey stuff. From there I kept looking, searching, for you know, the sound... the sound that you like... the sound that turns you on, the music that gets you excited, the song and bands you've always been waiting to find and hear. Green Day was an anomaly within this mix, and never much found its way onto the mix tapes I received or made. As I listen to Dookie now on my headphones, it still doesn't move me very much. I admit the catchiness of some of the songs, such as Longview. But perhaps I've heard them too many times, even if it wasn't me who was putting on the record. Despite this, many of the other bands that had been brought up on Lookout Records I really loved, and it was The Queers who probably remain my favorite. That was my first bonafide punk rock show as well, The Queers opening for Rancid. Probably not long after Dookie came out. And though the Rancid show was good, it was The Queers who really shined that night. Admittedly, part of my own dissing of Green Day back in the day, and now, was because of their popularity. With a chip on my shoulder as a middle class skater punk from the westside, I got irritated with all the people my own age who fell in love with it, but they didn't like the hard hitting and lyrically more devastating music of Bad Religion and the like. Well, now I don't need to be such a jerk about it, but I still find myself driven to comment on the band and album, as in this email. However, I'm reminded of the punk novel by Stacy Wakefield, The Sunshine Crust Baking Factory. Set in 1995, its about a young punk girl who goes to NYC and gets involved with the squatters and the underground hardcore music scene there, (hence the crust). "Sid teams up with a musician from Mexico and together they find their way across the bridge to Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Packs of wild dogs roam the waterfront and the rough building in which they finally find space is occupied by misfits who don’t know anything about the Manhattan squatting scene, Food Not Bombs, Critical Mass, or hardcore punk. But this is Sid’s chance and she’s determined to make a home for herself—no matter what." It was a fun coming-of-age novel with a romantic subplot, and the one thing I always remembered about it was how the main character talks about the guy she falls for, and how she can listen to Green Day with him, without pretending to always have to listen to the harder stuff like Nausea, Aus-Rotten, and Filth. Perhaps there is a good reason that part of the book stuck with me. In music as with reading: you can't always be delving into the Herman Hesse, Dostoyevsky, or the Bronte's. Sometimes you need to read some Mickey Spillane, Robert E. Howard, Ed McBain or what have you. In the same way you can't always be listening to Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage or Nurse With Wound. Sometimes you need to listen to Green Day. And as I listen to "When I Come Around" for the upteenth time, its not so bad. I guess today was my day to listen to this turd of an album that I reviled so much in my past. But maybe it doesn't stink as much as I remembered. I understand why it hit home with all the kids out in the suburbs. And why they covered this song at so many Battles of the Bands. This may be the first time since those days in the 90s when I listened to this album straight through. But the chances are good I might not listen to it straight through again for another thirty. It wasn’t that long ago that Lucien Kali Breverman turned thirteen. He was Klay to his friends because Lucien felt to uptown for him, even then. It was the same year he’d gone into seventh grade, leaving elementary behind, and wound up at Gimble High, two neighborhoods away in the spotty streets of West Forest. He used to walk to school, but now he had to take the bus.

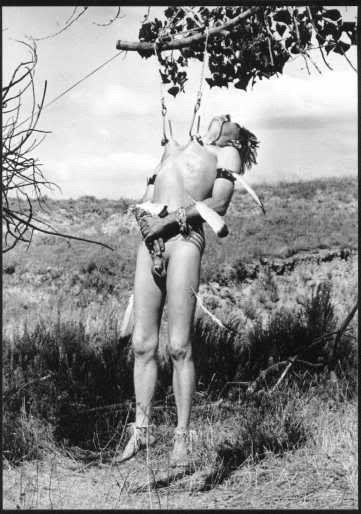

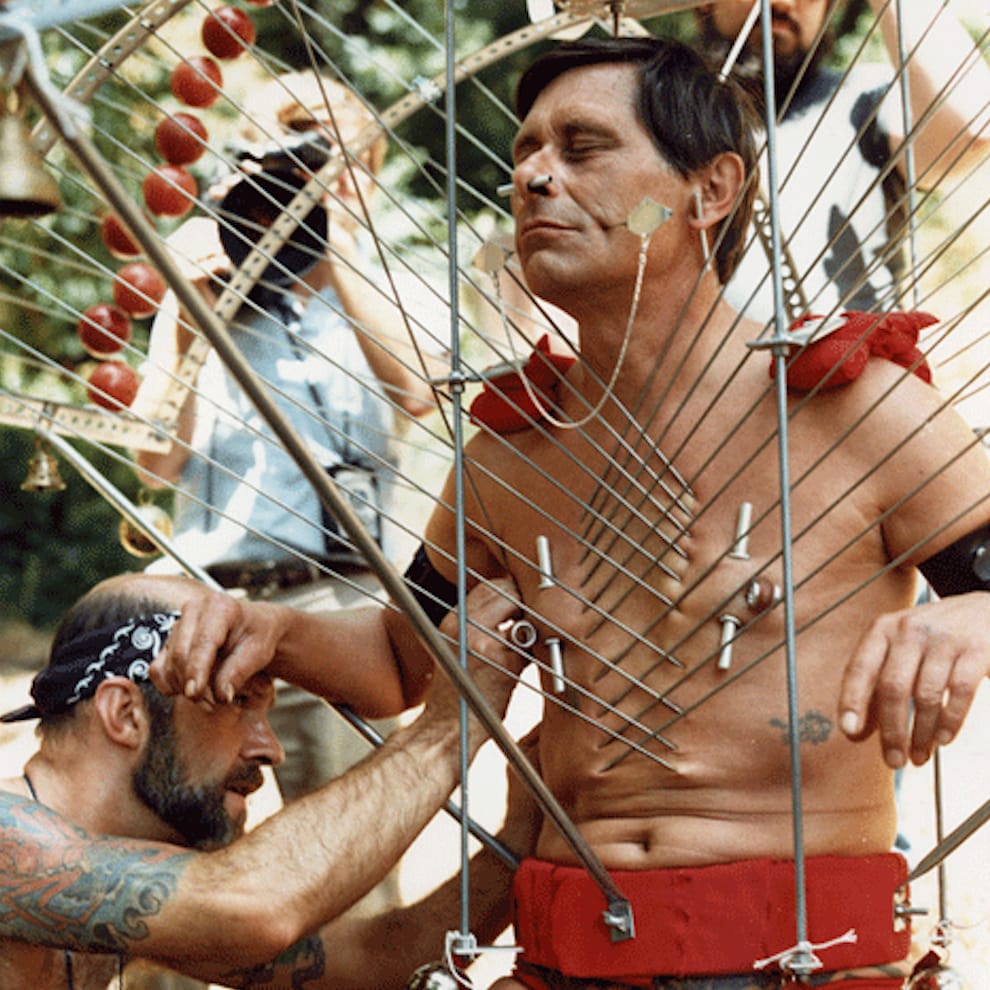

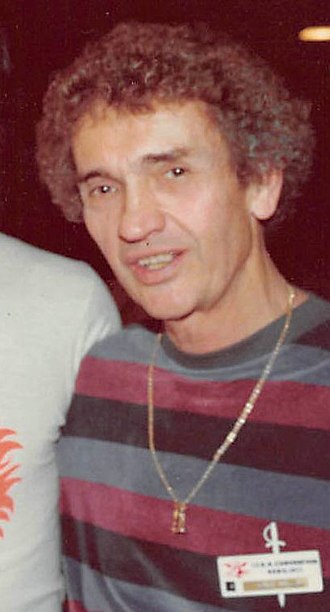

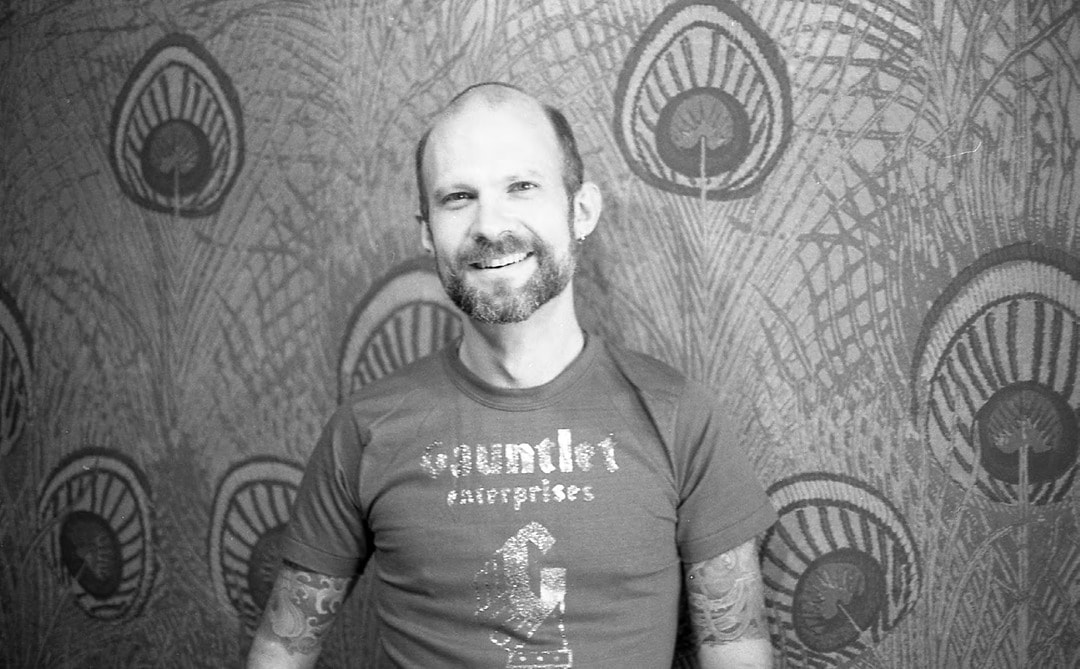

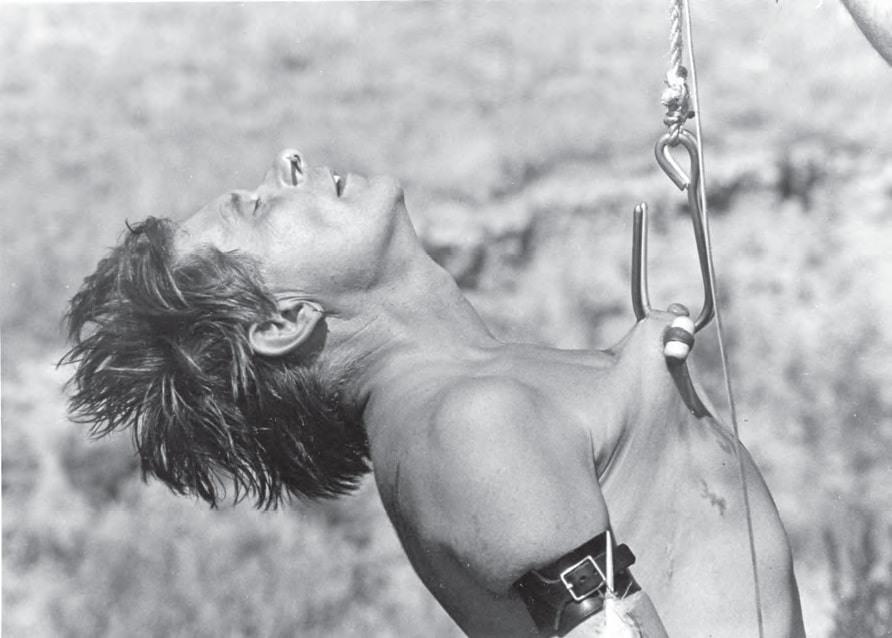

This was something he seldom looked forward to. In a car it would only take fifteen minutes or less to get home and up into his room where he could pick up his drumsticks and pretend Johnny’s face was the drum head, pretend Johnny was receiving a beating. Or boot up his Xbox to play Call of Duty and pretend it was Johnny who was the enemy. The problem was Johnny was always on the bus, and with all the stops, the trip took over an hour. Johnny was a sophomore and it was his second time being a sophomore. When Johnny was on the bus, it was never a smooth ride. Klay’s best friend Raelon had moved to a different neighborhood and rode a different route. The choice of who to sit with, just like at lunch, hung over him like a cloud of smoke and dust from one of the raging wildfires that had blanketed his city with smog over the summer. Sitting in the back was more fun, but it was also dangerous. That turf belonged to Johnny and his minions. School had just let out and Klay lingered on the back of the sidewalk waiting for the bus to fill up, hoping Johnny would get on first, so he could sit closer to the front. It was unfortunate that the front was the place where the droolers and other dweebs congregated, but the strategy had worked for him so far. He didn’t see Johnny. Maybe he’d skipped school. The bus was filling up so he had to move, he had to get on. Then he felt a hard knock to his shoulder, as Johnny bumped into him on purpose from behind. “Maybe we can sit together today, buddy, whaddya think of that?” Johnny said as he stood waiting for Klay to get on ahead of him. Klay hesitated and Johnny pushed him in the back. “Go ahead, get on.” Klay was flushed, and huffed his way on to the bus, hoping to find someone to sit next to who was sympathetic. The bus driver hadn’t once stepped in on Klay’s behalf to stop Johnny’s bullying, he never said a word to shut up the rowdiness in the back. The bus driver’s long hair often concealed headphones. He didn’t pay any attention to the kids, and barely paid attention to the road. He’d overheard his Grandpa Jason grumble to his Mom, who’d been discussing the situation after the second incident, and remembered him saying the driver was probably afraid of getting slapped with a lawsuit if he stepped in to reprimand the kids. As Klay walked passed the driver, he crossed the rubicon into the netherworld that was the school bus. Three seats back an earth angel awaited him, a radiant girl he had never seen before. “You mind if I sit here?” as he slid into the empty seat without waiting for a response. “Sure. Be my guest,” she said. “Would you do me a favor and switch seats, I need to sit by the window.” “If you really have to.” Johnny stood in the aisle and leaned over the girl to taunt Klay. “Oh, so you don’t want to sit with me? I guess you’re going to have to hide behind this puny little girl. Well don’t worry, you’re gonna catch these hands again soon enough.” He slammed his right fist into the palm of his left. “Well this ain’t the day, chief,” the girl said as she stood up. “Why don’t you go in the back derp, and shut your flapping face?” She was a lean five foot three, but a chill seemed to emanate from her, and Klay new it wasn’t a blast from the AC; no such thing existed on this bus. Then he caught a whiff of what smelled liked mud, like cold sod on a day of heavy October rain. A chorus of deep ooohs and laughter percolated around the seats, and someone said, “Come on now girl, you don’t want to trigger Johnny!” But there was something in her iciness that caused him to zip his lip and slink down into the back where he did shut his trap. “Thanks for that. I owe you one,” Klay said. “Yes, you do. Care to make it up to me?” “Sure,” he said, as he looked at her with care. “Did you just transfer here?” “No… It seems like I’ve been going here forever.” He smelled that scent of wet earth again though it hadn’t rained for days. “Will you walk me home?” she asked. He gave his ascent and asked “what’s your home room?” “302, with Mr. Hagg.” “Wait, I’m in 302. That’s Ms. Grundle.” She just shrugged and didn’t say anything else. He tried to continue the conversation, but she wouldn’t speak. He felt grateful for what she’d done, and felt like his luck had turned, because she was a smashing beauty. Her style was half-preppie, half-punk, and her eyes were emerald green. Her strawberry blonde hair smelled like fresh cut roses. Yet the longer he sat next to her, the colder he got. She didn’t say anything else until they got to the stop at Lake Grove Cemetery. “Let’s go,” she said and grabbed her bag off the floor. She managed to get off before him, and when he stepped onto the sidewalk he thought she’d disappeared. He turned around, and on the second turn, she was there again. He for sure needed a nap when he got home. He was tired, or maybe going crazy like his friend Raelon always said. In quietude she led him into the cemetery. Maybe she doesn’t want to go home, he thought. Maybe she wants to give me kiss, or make out. He’d heard of kids doing that in the cemetery, and he hoped to join their ranks. She took him along the winding paths, past the ponds and their geese, past the bone white mausoleums littered with orange maple leaves. She took him into a plot underneath a mighty oak as acorns crunched underneath his feet. No sound came from her. “Thanks for bringing me home,” she said and bent to give him a kiss. The wind picked up just then and she was wisped away, gone before his eyes. He looked down at his feet, bewildered, and noticed the fresh cut roses on the gray marble gravestone. Jenny Wailings Born January 15th, 1981, Died October 13th 1997 Beloved Daughter, Granddaughter, Sister He pulled out his phone and googled her name. She’d died in an accident while walking home along the train tracks after being bullied off the bus by the resident mean girl. The next year and every year thereafter on October 13th Klay would bring her fresh cut flowers. --Justin Patrick Moore Cincinnati, Ohio October 13, 2023 PDF File of Story "Your body belongs to you, and in the appropriate ritual, it has been given to you to explore the full dimensions of your being." -Fakir Musafar Putting a sharp pointy object straight through the skin is a time honored practice among us humans. Piercings have long been a way we have sought to make ourselves beautiful. Wearing jewelry through the skin has been a part of our aesthetics of adornment dating back thousands of years. But why do we pierce? The answer to this question has varied depending on the time and era. Some people have gotten piercings for magical, mystical and spiritual purposes; for others it is just a way of expressing themselves. Some get piercings for sexual pleasure, such as on the nipples or genitalia. There was a time in America when getting your ear pierced as a man, was seen as an act of outright rebellion. Getting another part of the body punctured was beyond the beyond of proper decorum, for either sex. Yet in other societies being on the receiving end of a needle for a piercing is a way to conform to the norms of the culture, be a part of the group, and fit in. It is much the same with those who belong to certain subcultures, such as punk, where a piercing can signify affiliation. Piercings started to regain prominence in western society starting in the seventies, and underpinning their revival was a strong current of magic. ENTER THE FAKIR The late Fakir Musafar was often called the father of the modern primitive movement, for his pioneering work in body piercing, modification, ritual and teaching. Fakir was born on August 10, 1930 as Roland Loomis on what was then the Sissiton Sioux Indian reservation in South Dakota, a baby of the Great Depression. There wasn’t a lot going on in Aberdeen, where he grew up, and by 1943, at age thirteen, he was a bored teenager, looking for something to do while the world was at war. He felt different, and knew there must be something different to discover out there in the wide world; something other than what was presented to him by straight-laced society. Loomis took to haunting the school library, in search of anything strange. In one of the libraries dusty and forgotten corners he found what he was looking for in some old issues of National Geographic Magazine. His imagination became captivated by the pictures and articles he saw of people from other times and places. There was one issue in particular, from the 1920’s, where he saw photographs of people in India who had pierced their flesh with hooks and hung suspended from a cross arm high up in the air. The thirteen year old wondered why they were doing this. He also wondered what it felt like. The imagery called to him, touched something deep inside his soul. A couple of years later Loomis learned that some Native American tribes also practiced piercing their flesh so they could either hang suspended from it, or be pulled for long hours against the these piercings in a ritual known as the Sun Dance. This set off an aha! moment for Loomis. The tribes who practiced these rites had been those of the Plains Indians, many of whom lived in South Dakota, his birthplace. These ceremonies had last taken place some fifty years before he was born. There are a number of commonalities across tribal cultures that held the Sun Dance. A sacred fire, smoking and praying with the sacred pipe, and fasting from food and water were all typical. The songs and dances used were passed down over many generations. Traditional drums and drumming accompanied the song and dance, the latter of which was seen as an arduous spiritual test. Some Sun Dances involved a ceremonial piercing of the skin, a further test of bravery and physical endurance. The pain and blood were seen as part of the sacrifice involved in the ceremony, that was used for the benefit of the tribe. Some dances involved going around a pole that the men were attached to by a piece of rawhide pierced through the skin of their chest. He also learned about the Okipa ceremony of the Mandan people of North Dakota. It was a four-day ceremony performed every year during the summer that retold their creation story. Like the Sun Dance, the Okipa involved dancing inside a lodge filled with their sacred objects, while men prayed, fasted and sought visions. The younger men demonstrated their bravery by being pierced with wooden skewers pushed the skin of their chests, and backs. These men were hung by ropes from beams in the lodge or from trees, while their legs were weighed down from other skewers sent through their thighs and calves. Crying was seen as cowardice. Those who could withstand these intense sensations the best went on to become leaders within the community. Loomis started hunting out the places where the Sun Dance and Okipa ceremonies had taken place, and went to visit them on his bike. He found they had left behind a psychic residue and that this residue seeped into his own life as he absorbed the energies from the places where the Lakota, Arikira and Sissiton peoples had pierced their flesh, sometimes in rites where they hung from a tree. Loomis got to know some of the trees, as some were still there, holding memory on the living land. This became a tremendous inspiration to the young man. He was so inspired by these discoveries he had to try piercing himself. He even felt like he had done these things before -perhaps in a past life. He claims his first experience of these past lives came to him at age four. His later anthropological studies gave confirmation to his feelings. So he started modifying his body. Loomis did his first permanent body piercing, on his penis, at age fourteen, conducted his first mini Sun Dance ritual and had an out-of-body experience as the result at age seventeen, and his first self-made tattoo at age nineteen. At first it was a private thing, and he kept it private, kept it secret for thirty odd years before he went public. While he pursued the inner calling of exploring the outer body his destiny had born him into, he also racked up some impressive skills inside the confines of the culture at large. He worked for the U.S. Army during the Korean War between 1952 and 1954, where he was an Instructor in Demolitions and Explosives. He taught ballroom dancing at Arthur Murray’s. Loomis picked up a B.S.E in electrical engineering from the Northern State University and an M.A. in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University, the city he’d moved to at age 25. His creative abilities as a writer helped him in his work in executive positions as an ad man in San Francisco. He also operated his own advertising agency in Silicon Valley for a spell. Yet there was also isolation and shame around the things he was doing in secret, and those came from fear. Fear, that if he let people in his interests and practices, he would be deemed crazy, institutionalized, locked up and the key thrown away. Through his extensive research into other cultures, and long talks with native elders, he had learned that his interest wasn’t something that should be considered a sickness, a perversion or a mutilation of the body, but a practice that could lead into what some traditions called a “state of grace.” Rituals of piercing could be used as a way to access different modes of consciousness. Loomis eventually came out of the closet as piercing freak, a process that started when he met Doug Malloy in 1972, an eccentric millionaire, and ally who proved to be the alloy that bound the disparate elements of the underground piercing scene together and brought them up to the surface. AN ECCENTRIC ALLOY Malloy was a man who led a double life. His first life was as Richard Simonton, an aficionado of organ music, steamboats, a family man and a businessman who worked for the Muzak corporation, selling their piped in sounds to corporations in California. The side of him that was Simonton led a fascinating life in his own right, but I don’t have space to get into that aspect of his personality in this context. Simonton tended to keep his fly zipped anyway with regard to his penchant for piercing his penis, except in sympathetic company, or when he wrote about the subject as Doug Malloy. His double life was also exemplified by his bisexuality. Of his many interests, Malloy had made a study of the New Thought movement, even going so far as to meet Ernest Holmes, author of The Science of Mind, in 1932. His interest in metaphysical and spiritual topics prompted him to traveled extensively in India and the Philippines where he explored Eastern thought-ways. His mind had always been bent towards the unusual and different. Adorning his body with bits of metal poking through the flesh wasn’t so weird. At some point he started getting pierced. In 1975 Malloy’s fictional autobiography titled Diary of a Piercing Freak came out, released by a publisher who specialized in fetish material. It was later republished in softcover as The Art of Pierced Penises and Decorative Tattoos. Malloy had also started to cultivate a network of like minded individuals. These included Roland Loomis, Jim Ward, Sailor Sid Diller and the Londonite tattooist Alan Oversby, better known by his alias Mr. Sebastian. Malloy had also organized the Tattoo & Piercing group (T&P) of ten to fourteen people or so who would meet once a month for a “show and tell.” Malloy had seen some photos of the experiments Loomis was doing with his body that dated back to 1944, and invited him to be a part of T&P. This group expanded the practice of piercing and tattooing as the individuals gathered would later help each-other execute further body modifications. Together they developed a lexicon around body piercing, what each type of piercings was called, and what the best practices and tools were to do them. Jim Ward, the other prong in the trifecta that catapulted the practice of piercing to what it is today in America, was a close friend of Malloy’s and co-founder of the T&P gatherings. WARDEN OF THE BARBELL In the course of his long time wandering, Doug Malloy had made a visit to Germany where meet Horst Streckenbach, better known as Tattoo Samy. Samy had been born in 1925 and got his first tattoo at the ripe old age of ten. By 1959 the rubble had stopped bouncing from the second world war and Samy opened a tattoo shop in Aschaffenburg. Later moved he moved it to the bigger burg of Frankfurt in 1964. There, one of Samy’s students was a guy named Manfred “Tattoo” Kohrs. Together they worked on developing some new styles of piercing jewelry, namely, the barbell. In time, Samy started to make trips to America, and on these visit’s he would come to LA to visit Malloy, who in turn introduced him to Ward and others in the T&P circle. Ward was born in 1941 in Western Oklahoma, moved to Colorado at age elven, and by the time he was 26, was in New York city where he joined a gay S&M biker group, the New York Motorbike Club. That’s where he got on the nipple piercing tip, and started studying how to make jewelry. Ward stated, "The first barbells I recall came from Germany… On one of his [Samy’s] first visits he showed us the barbell studs that he used in some piercings. They were internally threaded, a feature that made so much sense that I immediately set out to recreate them for my own customers." From his own studies, and from Samy’s innovations, Ward began to put his spin onto the piercing jewelry he was creating, including the fixed bead ring design. Meanwhile Malloy had encouraged Ward to start a business for piercing people and gave him the funds to do so. Ward ran this business at first ran privately, out of his own home starting in 1975. He dubbed his studio the Gauntlet. Malloy drew upon his contacts to help Ward build a clientele. Ward the placed ads for the Gauntlet in underground gay and fetish publications. His business started to boom. BODY MODIFIERS UNITED

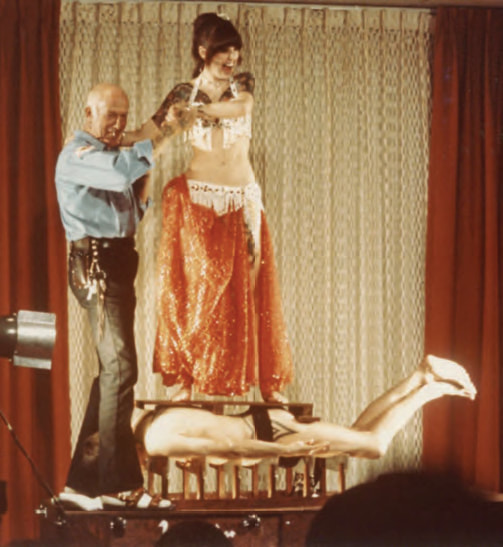

Next up on Malloy’s masterplan for modifying the body of the American republic was to host an International Tattoo Convention, in Reno, Nevada. He did this with the help of tattooists Sailor Jerry and Ed Hardy, and invited both Loomis and Ward to participate in the convention and show their piercings to the public. From this fixed point, 1977 on the timeline, piercings began to take off in tandem with tattooing. Malloy asked Roland Loomis to demonstrate the various practices he had begun to adopt from other cultures, such as laying on a bed of nails or bed of swords for the convention. Malloy didn’t think the name Loomis was memorable, and he encouraged him to change his name for the event so as to receive more publicity. Loomis had revered the 12th century Sufi saint whose name was Fakir Musafar. This saint had also practiced piercing himself as a way to get closer to the divine. Loomis adopted the name for himself and it stuck. His namesake was a mystic from Meshed, Persia (now Iran) who lived for sixteen years with six daggers embedded in his chest and back. He also had six horseshoes he kept suspended from twelve permanent piercings in his arms and shoulders. He believed, as did the man who took his name, that unseen worlds can be accessed through the body. From the unseen worlds the very source of being can be found. The stories around the original Musafar speak of how he was ridiculed and thought of as strange. He felt his message was going unheard and these rejections caused him to die of heartbreak. At the convention Loomis “came out” as body piercer and started to go by his adopted name. Fakir Musafar became the mystical and magical pioneer around these practices in modern times laying out a metaphysical and cross-cultural groundwork for body modification. Meanwhile, Jim Ward, bolstered by the success of his private practice, took The Gauntlet public in 1978, and laid the framework for the commercial success of piercing with its first business. All of this was synergerzied by the networking and business acumen and can-do spirit of Doug Malloy. Together these three exerted a lasting influence on the American body. As Musafar, Ward, and Malloy continued their crusade, they each also contributed further metaphysical, theoretical, and practical material to the growing scene. Malloy wrote the pamphlet Body & Genital Piercing in Brief, which continued the process of getting stories into circulation about the origins of various piercings, especially those relating to private parts. In 1977 Jim Ward started publishing Piercing Fans International Quarterly, which featured contributions from both Malloy and Musafar, as well as the coterie of metal clad pierceniks who had begun coming out of the shadows. Fakir Musafar continued to develop the ritual dimensions around piercing and other more extreme forms of body modification, transforming himself in the process into a contemporary shaman and father of the modern primitive movement. Along the way he racked up some impressive experiences, within the body, and while hanging from hooks, in the planes beyond out of body.  We humans have been tinkering on ourselves from the get go. We have made tools to manipulate our environment as well tools to modify our bodies. Since we first donned clothes, we have looked for ways to use our coverings as expressions of individuality on the one hand, and kinship with our families, tribes, extended clans and culture on the other. These adornments extend to jewelry and piercings, and tattoos. Just as rings, bracelets and necklaces may be given to mark a stage of life or commemorate an event, so too may a permanent tattoo be used to mark a stage of life or transition in time. Examples of tattoos, piercings and body modification go back deep into ancient times of our human record. Many types of body modification are done by people without giving it a second thought, that they are doing something to their body, it is so natural and ingrained in the culture. Hair styling and dying in a salon by older suburban women is one example, as is the daily ritual of putting on makeup. To shave or not to shave, that is another question of expression. Painting nails, or even bothering to clip them are others. Expensive surgeries for breast implants and tummy tucks, and a quick nose job for leading ladies and men, not to mention teeth whitening, are all examples of what may be considered acceptable forms of body modification in a materialist minded America intent on keeping up appearances. Many contemporary life saving surgical procedures wouldn’t be possible without some extent of body modification. Though there are many ways to modify the body, in the context of this article I’ll be writing mostly of those that were taken up in the punk community under the broader rubric and pan-subculturalism of “body modification” as relating to scarification, tatoos, piercings, implants, body suspension and some other techniques borrowed from traditional cultures and carnie culture. This first section deals strictly with tattoos. MY BODY, MY TEMPLE Those raised in a Judaeo-Christian worldview, and who have stuck with the tradition, tend to view the body as a temple. This view seems to originate from a Bible verse attributed to Paul (who to be fair, could be as brilliant spiritually as he was off base, in my opinion.) He wrote in 1 Corinthians 6:20 “Do you not know that your bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit, who is in you, whom you have received from God? You are not your own” (NIV). Yet treating the body with the respect due to a deity isn’t only found in Christianity. We can see echoes of this principle at work in Hinduism, with their highly evolved systems of yoga and Ayurveda, and other religions. It was the latter-day punk of the kitchen, Anthony Bourdain who said “your body is not a temple, it's an amusement park. Enjoy the ride.” I think both viewpoints are valid, and it is useful with any binary such as this to try and triangulate away from the extremes. What about a temple inside an amusement park, or an amusement park inside of a temple? The carnival happens before the holy season of Lent. Festivals are held on high and holy feast days, and I can see the return of the festival where the passions of the body are indulged in periodically as a necessary steam valve in our future world with more limited resources. As in the period of festival, the sacred and profane can both exist within the collective body. So too in the way we adorn and modify our individual bodies can partake of the sacred, the profane, and points in between, as it has throughout history. AN ELDER FORM OF ART Tattoos can rightly be considered one of the eldest forms of art. Our evidence for this goes way back. An Egyptian mummified priestess of Hathor known as Amunet was one of humanities oldest examples of a tattooed person for some time. She was doing her thing during the Middle Kingdom Period (2160–1994 BCE) and hung out with some other priestesses who got tattooed as part of a ritualistic process. In this time, tattoos were reserved for women, and may have been part of magical rites regarding fertility and rejuvenation surrounding the worship of Hathor. Egyptain menfolk started getting ink during the 3rd and 4th dynasties when the pyramids were being built. The Egyptians were influencers, being the center of civilization for some thirty odd centuries, and from there the practice of tattooing spread outwards to other cultures who came to trade and learn, going deeper into Africa, and over into Asia and Europe. Egyptians weren’t the first to make permanent marks on their body and the priestesses of Hathor had to give up their OG status when Ötzi the Iceman was discovered in the Ötztal Alps in 1991. Ötzi was dated to between 3350 and 3105 BCE. The tattoos found along the preserved skin of Ötzi were line and dot patterns. Researchers noted how the placement of these lines and dots were along acupuncture points. This points to the idea that he was not just tattooed for adornment, but also for spiritual purposes. Ötzi had a total of 61 tattoos. In 2018 tattoos were again found on Egyptian mummies using infrared that were of the same vintage as Ötzi. Numerous other ancient mummified bodies from other parts of the world have also been found with body modifications. This shows how widespread the practice was in early times. The nomadic Ainu people brought tattooing into Japan around 2000 BCE. On those islands the magical aspect of the practice seems to have been downplayed in favor of simply having and enjoying them for their aesthetic beauty. Over the centuries the Japanese developed a tradition of tattooing that involved large pictures over big swathes of the body, creating what is now called a “sleeve.” This tradition was adopted by the Yakuza between 1600 and 1800 and still continues to this day. Known as irezumi in Japan, traditional tattooist will still "hand-poke" there work using ink is inserted beneath the skin with the traditional tools of sharpened needles made of bamboo or steel. Getting tatted up this way can take years to complete. Starting between 1200 and 400 B.C. tattooing migrated from China and Russia to the Picts and also into the Celtic countries of Scotland, Ireland and Wales. The Celts liked the color blue and used a substance known as woad to imprint symbols from their culture onto their body. These included spirals, labyrinths, and knotwork. Native American tribes were also invested in the practice of tattooing and associating it with spiritual power. They would prick themselves with sticks and needles and then rub soot and dyes into the open sores to form their pictures. Often these pictures were made in commemoration of battles they had fought or they were of animal powers whose strengths and abilities they wished to emulate, or of traditional symbols whose magic they wished to imbue into their life. At the same time tattoos were flourishing in North America they were also flourishing across the Polynesian islands. The word tattoo itself comes from “tatu” as used by Polynesians and picked up by Captain James Cook -who also helped spread the tattooing habit to sailors, and bring it back into practice among that group after his visit to the islands in 1769. The Polynesians were all about the spiritual power of a tattoo, and they believed that it made the invisible powers a person had in the spiritual world visible on their body. A rich tradition of tattooing was carried out by these peoples, and it often involved rites of passage between father and son. It was in Tahiti aboard the Endeavour, in July 1769, that Cook first noted his observations about the indigenous body modification and is the first recorded use of the word tattoo to refer to the permanent marking of the skin. The Captain’s log notes how, "Both sexes paint their Bodys, Tattow, as it is called in their Language. This is done by inlaying the Colour of Black under their skins, in such a manner as to be indelible... this method of Tattowing I shall now describe...As this is a painful operation, especially the Tattowing of their Buttocks, it is performed but once in their Lifetimes." Sir Joseph Banks, the Science Officer and Expedition Botanist aboard the Endeavour was taken with the idea of getting a tattoo himself. Banks had first made his bones on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. Then he signed up for Captain James Cook's first great voyage that lasted between 1768–1771 where he visited Brazil, Tahiti, and then spent six months in New Zealand and Australia. He came back with a tattoo upon him and heaps of fame for his voyage and work. A number of rank-and-file seamen and sailors came back with tattoos from their voyages, and this class of people began to adopt the practice further, helping to reintroduce tats to Europe, where they spread into other branches of military men, and into the criminal underworld. Yet tattoos had already made some headway back in Europe among the aristocracy by another route. In 1862 Albert, the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, had a Jerusalem Cross tattooed on his arm on a visit to the Holy Land. Christian tattoo traditions can be traced back to the Holy Land, to Egypt and the Coptic tradition all the way back to the 6th and 7th century. The practice was passed on to a variety of Eastern communities including the Armenian, Ethiopian, Syriac and Maronite Churches. It is a standard practice within todays Coptic Church to get a Christian tattoo and show it as proof of faith in order to enter one of their churches. At the time of the Crusades this tradition was passed on Europeans who had come to the Holy Land where they received tattoos as part of their pilgrimage to the Holy City of Jerusalem. These pilgrimage tattoos were one of the routes the practice went into the European aristocracy. Edward the VII got one after his pilgrimage, and George the V followed suit. King Frederick IX of Denmark, the King of Romania, Kaiser Wilhelm II, King Alexander of Yugoslavia and even Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, were all tatted up, often with elaborate Royal Coat of Arms and Family Crests. LE FREAK Meanwhile in America Martin Hildebrandt learned the art of tattooing while in the U.S. Navy, which he had joined in the 1840s. During the Civil War he fought with Union soldiers in the Army of the Potomac, and often traveled from camp to camp tattooing his fellow enlisted men. The Civil War veteran, Wilbur F. Hinman, wrote that it was common for regiments to have tattooists among them who inked their fellows with "flags, muskets, cannons, sabers and an infinite variety of patriotic emblems and warlike and grotesque devices." It was also common for the soldiers to have their names and initials marked permanently on their body to serve as a way of identification should they be killed in action. After his service Hildebrandt opened up a shop in New York City where he made tattooing his full-time job. His parlor was in a tavern on Oak Street in Manhattan, and opened between 1870 and 1872 and is most likely the first shop of its kind in America. Using vermilion and India ink, he tattooed people in black and red from across the spectrum of society. Nora Hildebrandt, who became his common law wife, also became a tattooed lady inked up by Old Martin. In 1885 she left to go on tour with a sideshow and he got arrested for disorderly conduct and was taken to the Insane Asylum where he died in 1890. But don’t blame that on his profession. The carnie culture surrounding circuses, sideshows, and dime stores, with their freaks and tattooed ladies were another medium through which the practice of getting marked up permanently for life started to spread throughout the United States. Becoming a tattooed lady was good work at the time, especially for those who wanted to have a bit more clink in their pocket and live life on their own terms. Dime stores, freakshows, and dime museums would often put ads in the paper looking for tattooed ladies, because they had become popular attractions. In the years that closed out the 19th century and opened up the 20th, it didn’t cost a fortune to get a tattoo, and if it was used as a way to make money, could be an investment. A full body job could be completed in less than two months and only set a gal back thirty buckaroos. Yet, if a tattooed lady was popular, she could rake in a Benjamin or two a week, give or take a little. Teachers in 1900 only made about seven dollars a week with room and board. Secretarial jobs might only earn about twenty-two dollars a week. Getting tatted up and showing it off to an eager public made sense, especially for those who wanted to leave behind traditional sex roles. By the 1940s however, the craze surrounding tattoos had again abated for a time. People who had them were often considered outcasts, less-than’s, and, of course, freaks. Yet bikers, motor cycle clubs and other greaser types kept the tradition alive in the 1950s alongside the usual suspects of sailors, military men, and underworld inhabitants. The cool factor started to creep back into the practice in the 1960s when Janis Joplin and other musicians, such as those in the Grateful Dead, started getting tatted up. Starting in the 1970s, tattoos started to move further into the mainstream and to people from all walks of life. Part of this had to do with the proliferation of subcultures where tattooing was seen as an acceptable form of self-expression. Freedom loving hippies, nihilistic punks, rappers and hip-hoppers and transgressive industrial music heads were all making modifications to their bodies. In the 1980s tattooing got a magical boost from Thee Temple Ov Psychic Youth (TOPY). TOPY was an artistically-oriented occult and magic group that emerged from the industrial music subculture surrounding Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV. One dimension of it was that it was like a "fan club" for Psychic TV except instead of creating followers their intention was to create leaders and get people doing their own individual creative work. Active between between 1981 and the early 1990s, the people involved were also heavily interested in piercing, body modification, tattoos and what I have taken to calling "gender blending". They did a lot of magical and occult work around these practices -and with their added influence, body piercing and tattoos went from something being done by counterculture freaks to being de rigeur. Their magic worked. The same could be true of some of their ideas about gender. TOPY is another example of a fringe group doing magic that went on to have a wider influence on the culture at large. They often included ritual elements as part of their piercing and tattooing works aligning themselves with the retro cutting edge of modern primitivism. CIVILIZED PRIMITIVES